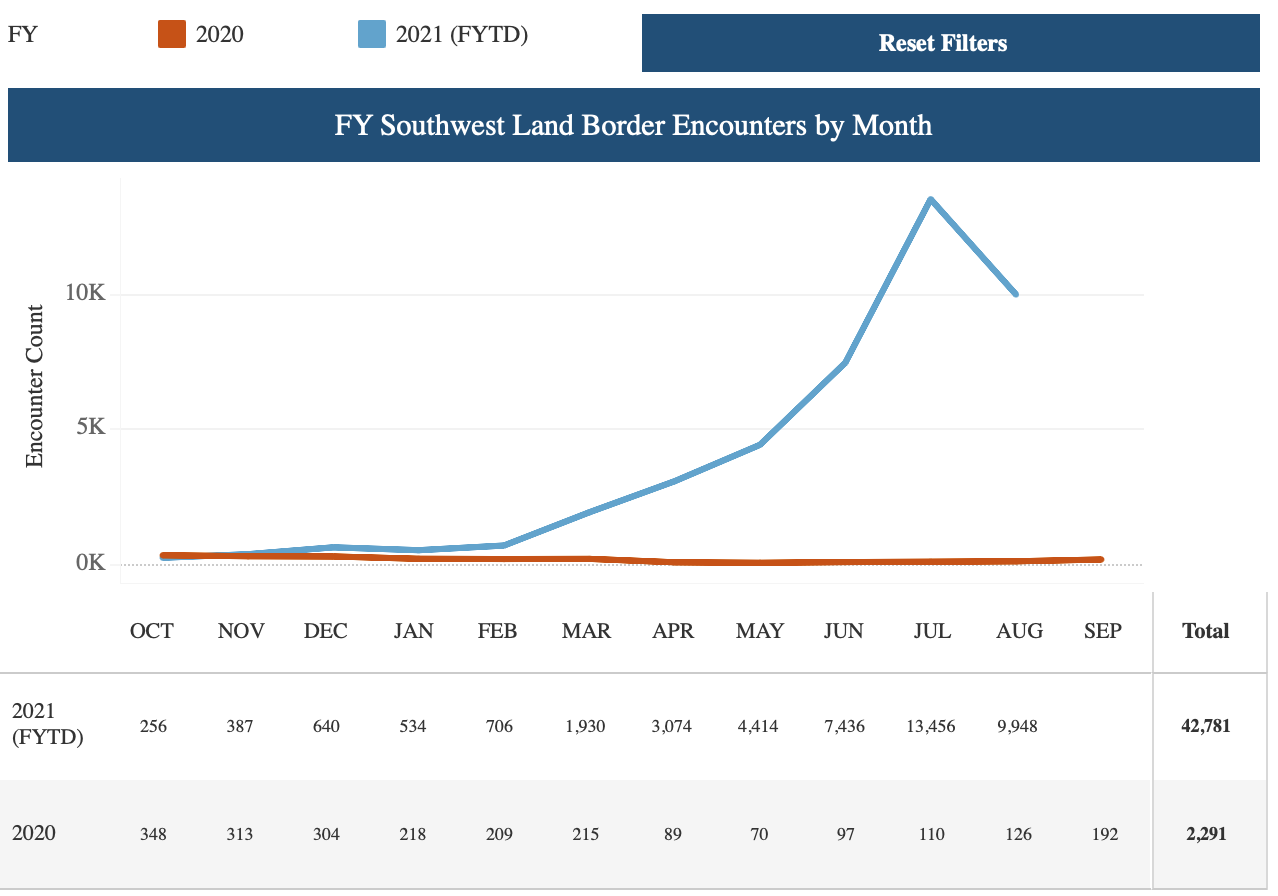

There has been a notable increase in migration from Nicaragua toward the United States in recent months. According to an Associated Press review of Customs and Border Statistics, the number of Nicaraguans who have been picked up by Border Patrol during the current fiscal year is 33,000, with 7,325 encounters just in June and 13,000 arriving in July [Note: Updated figures with graphs at end of post]. This represents a significant increase over recent migration from Nicaragua. Indeed, for most of the period since the Sandinistas returned to power in 2006, annual encounters of Border Patrol with Nicaraguans hovered around 1,000.

The only reason for the increase in migration from Nicaragua explored in AP and Reuters investigations is the claim that people are fleeing political persecution. This has become the latest media narrative on Nicaragua - i.e., a political crackdown is leading to an exodus from Nicaragua. Like many other narratives over the last three years, this is not really true, or, at least it is far from the whole story. It is true that there has been a spate of arrests of political opposition figures since June. One can argue about the validity of these arrests, but they’ve clearly happened and have been widely condemned outside the country. There has also been an increase in people leaving Nicaragua, represented by an increase in people arriving at the US/Mexico border. The fact that both things are happening does not mean one is causing the other, as anyone who survived a freshman statistics class can tell you - correlation is not causation.

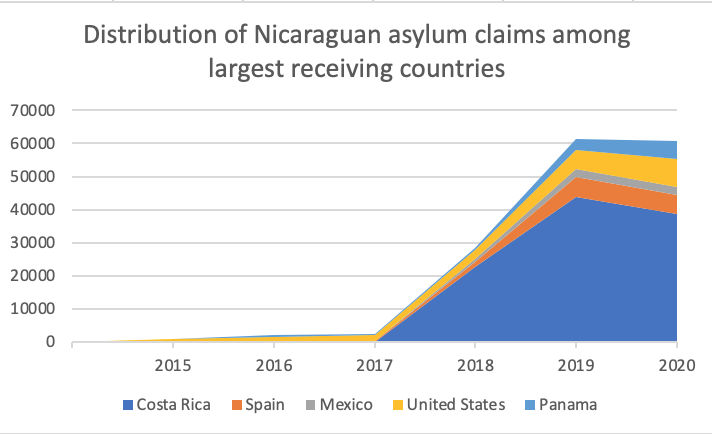

The increase in people seeking asylum from Nicaragua is undeniable. Since the political crisis erupted in April of 2018, the number of Nicaraguans seeking asylum around the world has risen dramatically. In 2015, for example, the number of people from Nicaragua seeking asylum across the globe was 1,232; in 2017 it was 2,722. In 2018, however, the number jumped to 32,000 and then peaked in 2019 at 67,000. The number of asylum seekers has actually fallen since. The majority of these claims have occurred in Costa Rica, with significant numbers of people also seeking asylum in Spain, Mexico, Panama, and the United States. While there was an increase in border crossings in the United States during the 2018-2019 crisis, it was far below the current bump - and the situation was far more volatile then.

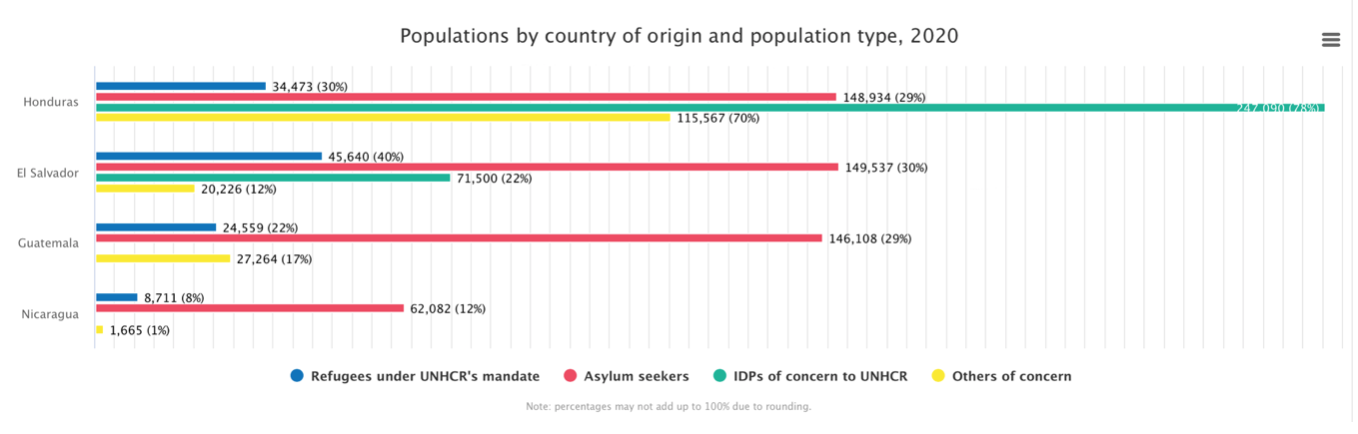

As high as these numbers have been by Nicaragua’s recent standards, when compared to other countries in Central America the figures are low. The chart below shows UN data for different categories of forced migration, internal and external, in Central America for 2020. Not only is Nicaragua well below all of its northern regional neighbors concerning the number of people seeking asylum, and/or claiming refugee status, there is basically no internal displacement, and few “other” categories of concern in Nicaragua. Compare this to Honduras, for example, where internal displacement approaches 250,000 people on top of the 180,000 combined asylum and refugee claims.

Honduras is, of course, not a standard of good governance for anyone I know. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the United States continues to tiptoe around abuse in Honduras, as well as Guatemala, (with its own new restrictive NGO law) and El Salvador (where President Bukele has been locking up opposition political figures as well).

It is also instructive to compare the number of asylum claims vs the total number of people migrating. Doing so makes clear that asylum is not the main reason people are leaving Nicaragua - not even during the worst of the political conflict. The case of Costa Rica is somewhat unusual but still instructive. The tens of thousands of asylum claims from Nicaraguans in Costa Rica need to be viewed alongside the annual 800,000+ border crossings between Nicaragua and Costa Rica that were the norm before COVID-19 as Nicaraguans routinely sought temporary work in Costa Rica. Indeed, the majority of asylum claims in 2018 were from people already living in Costa Rica at the time of the crisis who did not want to return. They were not all people fleeing the turmoil, though clearly many did not want to be pushed into it.

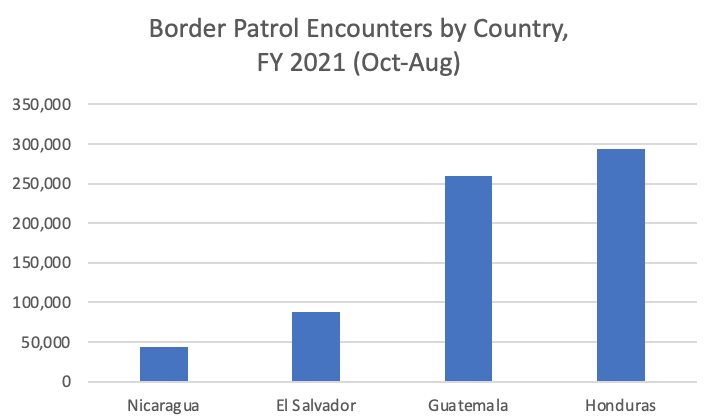

Within the United States, the notable increase in Border Patrol encounters of Nicaraguans reported on by the AP and Reuters (up to 33,000 so far this fiscal year) is also dwarfed by encounters from Honduras (242,000), Guatemala (218,000) and El Salvador (73,000). In all three cases, the numbers this year represent a dramatic increase over already high numbers from previous years. Encounters with people from Honduras are up 600% over the same time period last year, for example. In total, 1.2 million people have been encountered by Border Patrol during the current fiscal year, which doesn’t end until September 30. It is already the highest total in nearly 20 years.

So, what we are witnessing at the US border is an increase in migration across the board from Central America, as well as Haiti, Cuba, Venezuela, countries of Africa and South Asia - not just Nicaragua - and within this increase, encounters with Nicaraguans remain well below those of countries in northern Central America, much as they have for nearly two decades now. Political conflict is part of the explanation for migration from all of Central America, including Nicaragua. But it is pretty clearly far from the whole story.

So what else is going on?

From a regional perspective, there are a number of rather obvious push factors leading to an increase in migration over the last 6-12 months. So obvious, in fact, that one must wonder how they escape the investigative framework of journalists trying to isolate Nicaragua. Firstly, COVID-19 has led to a squeeze on domestic markets, disrupted international trade, and wrecked tourism, which had become a significant generator of employment for Nicaragua in particular. Secondly, there is widespread environmental devastation that is affecting nearly every corner of the globe. In Central America, this has translated into recurrent droughts, and more recently, the widespread destruction of crops by hurricanes Eta and Iota in November last year. Less an issue in Nicaragua, but devastating in Guatemala has been the explosion of parasites that have destroyed coffee harvests - an infestation largely blamed on shifting climate patterns.

All of these trends place added stress on people who see their livelihoods threatened or destroyed. In Nicaragua over the last two years, the government has also been under further pressure as the result of US sanctions, which have taken a bite out of multilateral financing for social programs. Even during the worst of COVID-19, the health sector in Nicaragua received nothing from the World Bank, while the Inter-American Development Bank provided only limited support. Nicaragua’s rightly celebrated gains in reducing poverty, extending free healthcare and education, investing in affordable housing and so on, are under threat as a result of all of this.

For Nicaraguans out of work, Costa Rica has historically been a place they can go for seasonal employment in agriculture and in the service sector. This is no longer the case. Costa Rica has been hit hard by COVID-19, especially in areas like tourism. There are now more Nicaraguans returning from Costa Rica than traveling there, and overall border crossings are way down. From 800,000+ crossings, split between coming and going, in 2018 and 2019, in 2020 the number of crossings was just over 270,000, with 143,000 Nicaraguans returning, versus 130,000 going to Costa Rica. The numbers for this year are not complete, but show a similar trend.

Far from a mass exodus to escape persecution, the people who are leaving Nicaragua today are mostly escaping a context of increased impoverishment, made worse by US sanctions, COVID-19 and natural disasters. All of this, coupled with an effective shutting down of temporary work opportunities in Costa Rica, means more people are heading north. It is, thus, a huge oversimplification to identify the source of migration as people fleeing a “crackdown” while ignoring these other factors. And compared to the rest of the region, Nicaragua is still doing better.

What the simplistic narrative does do is feed into the idea that the solution to migration from Nicaragua is a change in government. The reality is quite the opposite: If we want to see an actual surge of migration from Nicaragua, increasing sanctions or employing other interventions to force a change in government is the way to do it. People throughout the region are fleeing economic collapse and political instability - far fewer from Nicaragua, where the government has done demonstrably better at providing a safety net. So, if migration is the concern, squeezing Nicaragua further makes no sense. As it is, journalists from the US should at least be asking what the impact of US policy has on these trends, and other regional dynamics. Singling out Nicaragua in this way makes no sense.

UPDATED Numbers, Tables showing trends for the year

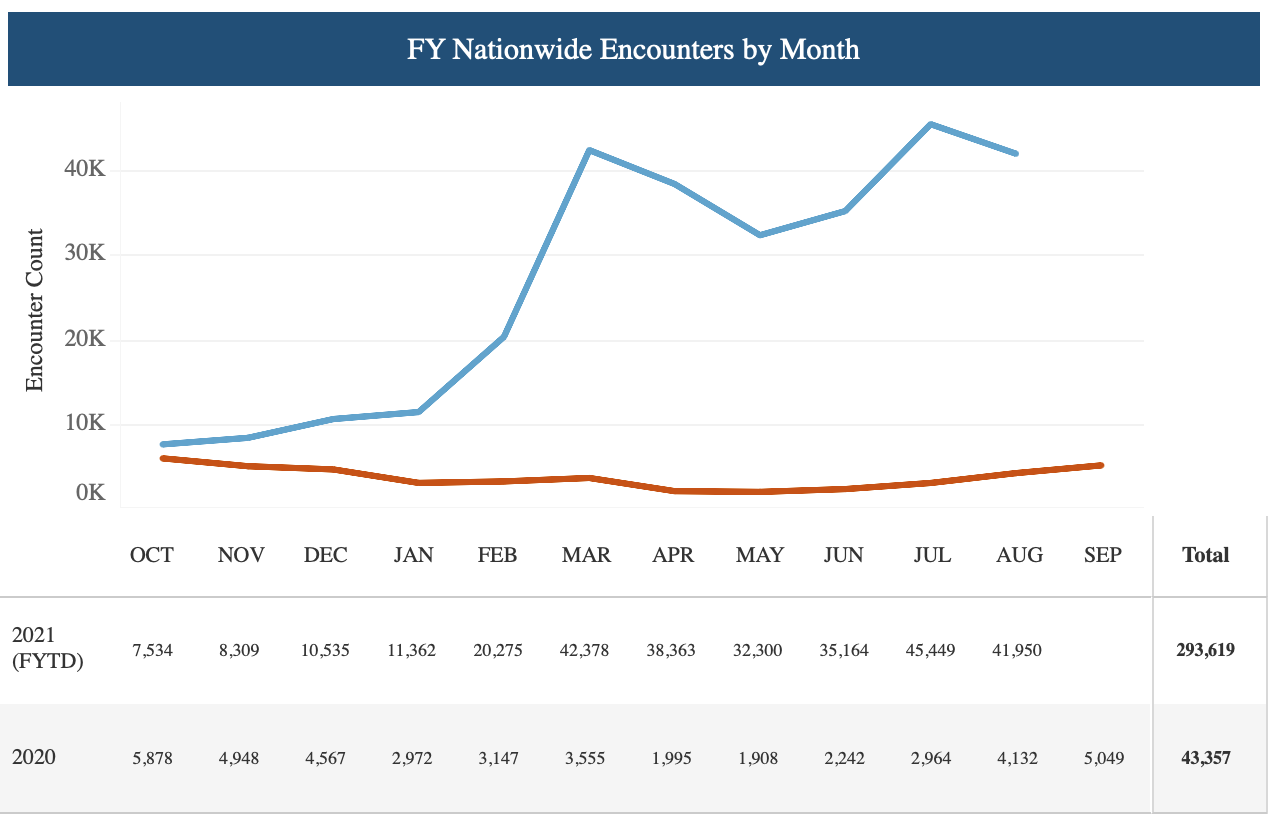

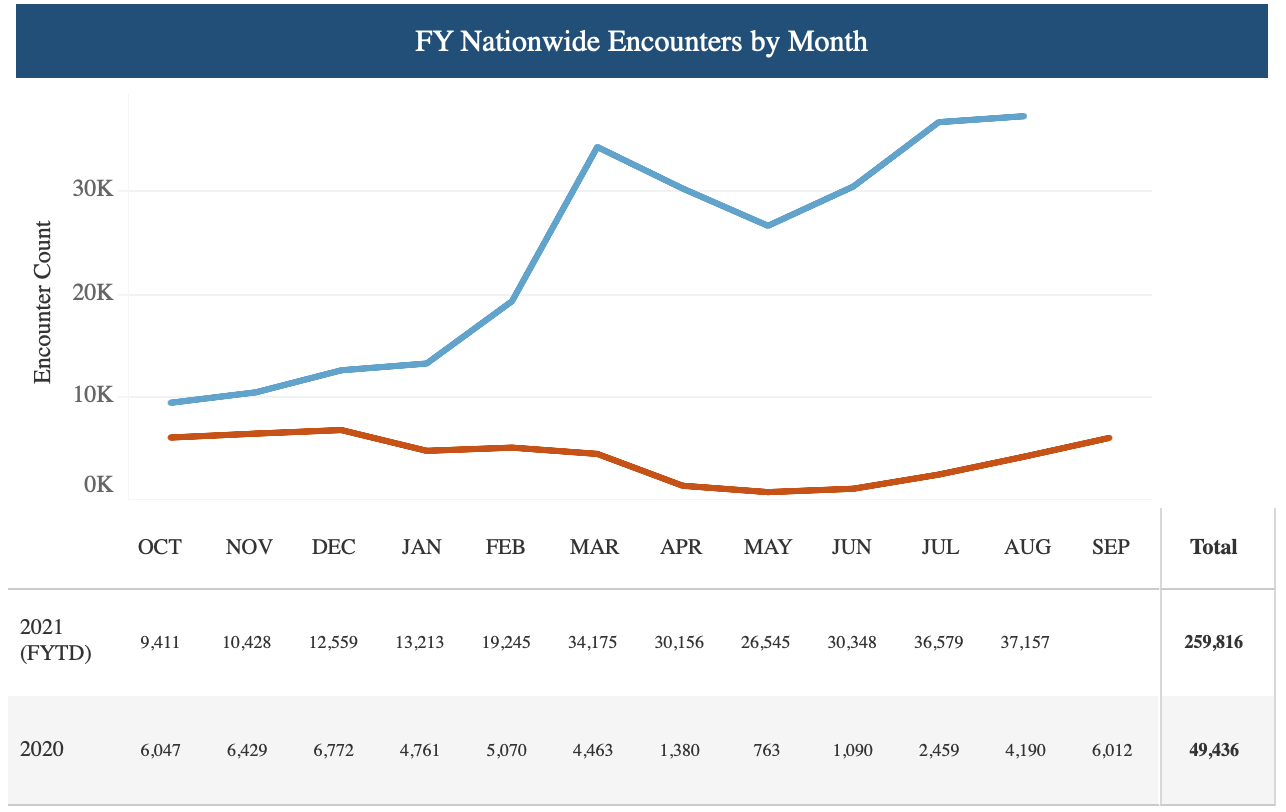

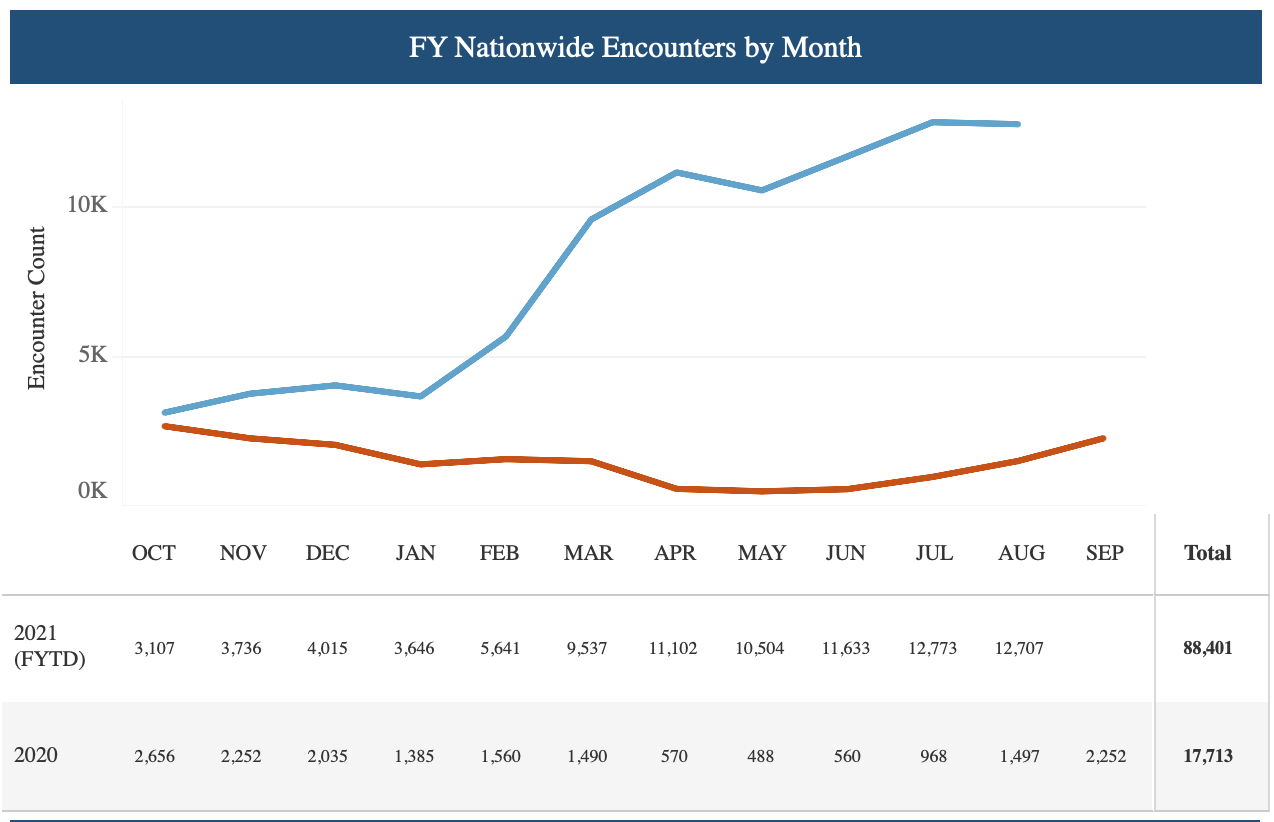

Note all countries have seen a dramatic increase in FY 2021 over FY 2020. Also note that from every country there is a significant bump in February/March. This is just to make the point that the increase in migration from Nicaragua is part of a regional trend - and not a unique increase in migration.

Over all year to date

By month, by country

[caption id="attachment_9753" align="aligncenter" width="800"] Nicaragua[/caption] [caption id="attachment_9750" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

Nicaragua[/caption] [caption id="attachment_9750" align="aligncenter" width="800"] Honduras[/caption] [caption id="attachment_9751" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

Honduras[/caption] [caption id="attachment_9751" align="aligncenter" width="800"] Guatemala[/caption] [caption id="attachment_9752" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

Guatemala[/caption] [caption id="attachment_9752" align="aligncenter" width="800"] El Salvador[/caption]

El Salvador[/caption]

Comments

Are Nicaraguan ... (not verified)

[…] for the Quixote Centre (9/17/21), Tom Ricker points out that attributing increased Nicaraguan migration to a political crackdown […]

Anarchist news ... (not verified)

[…] for the Quixote Centre (9/17/21), Tom Ricker points out that attributing increased Nicaraguan migration to a political crackdown […]

Are Nicaraguan ... (not verified)

[…] for the Quixote Centre (9/17/21), Tom Ricker points out that attributing increased Nicaraguan migration to a political crackdown […]

Communist news ... (not verified)

[…] reported in Western media as massive emigration due to government crackdowns, which is demonstrably false. Since the failed US-backed coup, the Sandinista government has gone into hyperdrive to recover the […]

Sandinistas Poi... (not verified)

[…] The issues that will determine election outcomes are straightforward. Nicaraguans are concerned, among other things, about their economic well-being. The Nicaraguan economy’s strong and enviable financial performance came to a screeching halt due to the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 2018. As a consequence, thousands of people have left the country in search of work and economic stability—something that continues to be cynically reported in Western media as massive emigration due to government crackdowns, which is demonstrably false. […]

Anarchist news ... (not verified)

[…] The issues that will determine election outcomes are straightforward. Nicaraguans are concerned, among other things, about their economic well-being. The Nicaraguan economy’s strong and enviable financial performance came to a screeching halt due to the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 2018. As a consequence, thousands of people have left the country in search of work and economic stability—something that continues to be cynically reported in Western media as massive emigration due to government crackdowns, which is demonstrably false. […]

Migration from ... (not verified)

[…] I wrote about migration from Nicaragua last October, an important dynamic in the increase in people heading north was the decline in people heading […]