Under pressure from the US, and with a large financial incentive, Panama is attempting to control the flow of migrants in its territory through deterrence and deportations.

Officials estimate that that 420,700 migrants have crossed the treacherous Darién gap this year, set to double the amount of people in 2022. According to Panama’s security minister, more than half of those migrants were children and babies.

President Biden has proposed a pilot program to direct $10 million in foreign aid to help Panama carry out deportations. The chairs of the Black Caucus and Hispanic Caucus issued a statement this week calling for a halt to this proposal, which awaits Congressional approval.

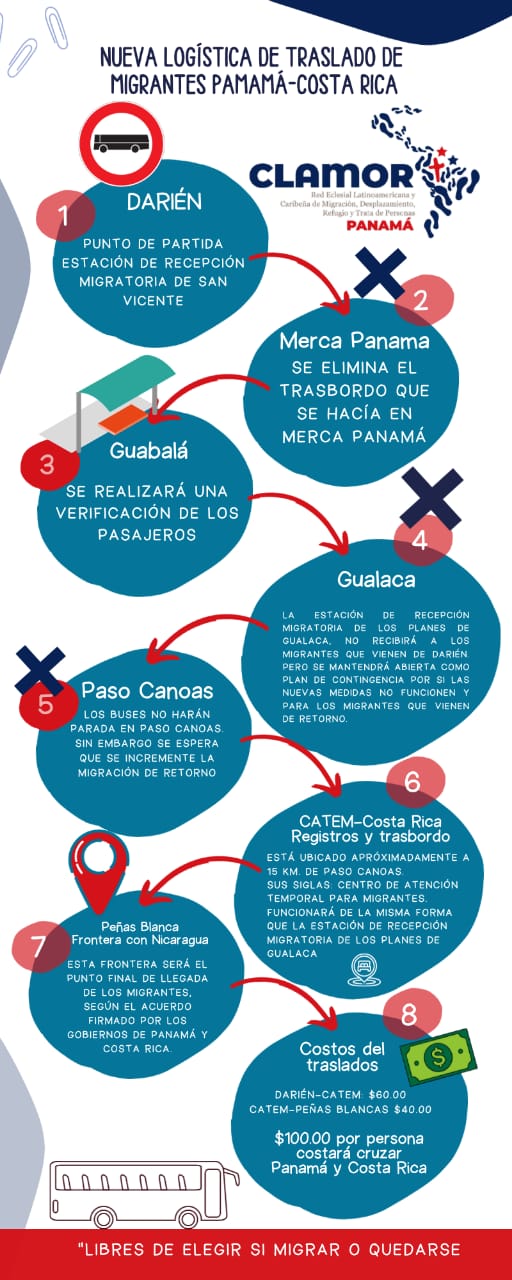

This week, Panama and Costa Rica announced a plan to quickly bus migrants northward. Panama hopes to disincentivize smuggling networks and alleviate pressure on its reception centers, but this is also likely an effort to push migrants out of Central America as quickly as possible.

This busing system is nothing new, as we’ve explained in a past blog, but this signals a major expansion in the program. As Panamanian officials intercept migrants at the mouth of the Darién rainforest, they bring them to a government-run “reception center”, which the Quixote Center team visited this past March.

For $100 a person, migrants can choose to be bused straight to Costa Rica, with an identity check in Guabalá. This eliminates the stops in Merca Panama and Paso Canoas, as well as Gualaca, the site of the deadly bus crash in February. Migrants pay $60 a person to go to a “migrant care center” on the other side of the Costa Rica-Panama border, and $40 more to Peñas Blancas on the Costa Rica-Nicaragua border. Those without money are out of luck.

“The day began in Paso Canoas without migrants in the street, or waiting in line at Western Union,” said Rafael Lara, facilitator for our partners at the Franciscan Network for Migration’s Panama team.

“In the Darién, those who don’t have the $100 to pay [for the bus] leave the San Vincente Reception Station have begun walking to Panama City, according to the Claretian missionaries in the area. Yesterday we met with Panama’s [Department of Migration] and we are informed that both the Medalla Milagrosa Shelter and the Paso Canoas soup kitchen should continue to operate, as they anticipate that the return migration of deportees from the United States will increase.”

Panama has also announced new deterrence efforts, including plans to ramp up deportations through chartered flights and increase infrastructure in the jungle. Similarly, Mexico has agreed with U.S. officials to begin deporting citizens of Venezuela, Brazil, Nicaragua, Colombia and Cuba, pending negotiations with these countries.

The Biden administration has also announced that it will resume deportations to Venezuela and build new border wall. However, neither of these measures, nor the ongoing restrictions on asylum access, are enough to deter Venezuelan migrants from making the dangerous journey into Panama.

As history and the current moment have shown, deterrence policies, deportations, and closed borders do not prevent people in situations of violent danger or extreme poverty or both, from dreaming of a better future. We suggest that rather than strategize new ways to keep migrants out, leaders across the region work together to both address the root causes of migration and ensure humane treatment and welcoming in the interim.

Our RFM partners in Panama are working to open the country’s only non-profit-run migrant shelter. They also serve migrants throughout the country and distribute humanitarian supplies in the Darién. The need for services is only likely to grow. You can donate here to support their work.