The following was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

In the Rio Grande Valley, plans for a border wall ignite fight between church and state

"In the Rio Grande Valley, plans for a border wall ignite fight between church and state" was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

MISSION — In these parts, Father Roy Snipes is known as the “cowboy priest.”

It’s not a bad moniker for the 73-year-old clergyman, who wore a loose set of black clerical clothes as he wandered over with his two mutts on a recent afternoon to La Lomita, a historic adobe church on the banks of the Rio Grande.

Sitting on the pews inside the tiny white chapel, where he made his final vows to the church nearly four decades ago, Snipes took off his Stetson hat and let out a sigh.

“Everybody sees this as our mother church. It's sacred in our memory," he said. “But who knows—the spell could be broken. The atmosphere could be spoiled.”

That's because the government is moving to expand border fencing here in Hidalgo County, casting a shadow over the future of the chapel and threatening to leave its fate in the hands of government bureaucrats in Washington.

Customs and Border Protection awarded contracts earlier this fall to construct several dozen miles of border barriers, including a six-mile stretch of concrete and steel fencing that will cut through a nearby state park and the National Butterfly Center.

A spokesperson for the federal agency said that this stretch of the wall will only go south to Conway Road in Mission, about half a mile short of La Lomita.

But with federal authorities already trying to survey the land around the chapel, Snipes fears that they may try to permanently take over La Lomita and extend the wall on a levee road just north of it.

That would leave the chapel cut off from the rest of town, instead stuck between the barricade and the Rio Grande.

And that means that Snipes, who still uses a flip phone and spends his free time steering a decades-old motorboat, has emerged as an unlikely player in a national fight that locally is pitting two of the region's most influential forces – the Catholic church and the U.S. immigration apparatus – against each other.

Just before Thanksgiving, federal authorities moved to take control of about 67 acres around the chapel, arguing that they need “immediate possession” of the land in order to investigate it for future use — including, perhaps, permanently seizing it to build the wall.

“Time is of the essence,” government lawyers said in a Nov. 20 court filing.

But Snipes and his fellow clergy have so far resisted those efforts in court. It's just one of several legal battles by religious groups in the area opposing the government's attempts to beef up border security. An oratory and a local Catholic high school have both sought legal action to prevent the government from surveying plots of brush land on their properties.

The church argues the government doesn’t have the proper authority to take over the land, but its main opposition is deeply rooted in religion. A wall would keep people from accessing the chapel to practice their faith and violate freedom of religion under the First Amendment, religious leaders said. And using their land to build the wall would go against Catholic values.

“The Church is not angry with anybody, just interested in remaining who she is,” said Bishop Daniel Flores, who leads the Catholic Diocese of Brownsville. “A wall is not an intrinsic evil, but it is a prudential social disaster.”

Snipes, whose beat-up van is covered in stickers that say “no wall between amigos,” said that his opposition to the wall is not so much about politics as it is about the gospel.

“Our message is ‘come on in, we’re trying to make you feel at home,’” he said. “Walling out our neighbors on the south side is just as sacrilegious as keeping us from our sacred shrine.”

Federal authorities said in court filings that they want to use the land around La Lomita to “conduct surveying, testing, and other investigative work” over a 12-month period in order to plan for roads, fencing, vehicle barriers and cameras designed to help secure the border.

To justify the taking, they cited President Donald Trump’s February 2017 executive order to “build the wall” as well as a 2006 congressional mandate. They also argued that their activity would not keep parishioners from their regular activity inside the church.

A CBP spokesperson declined to comment because of ongoing litigation. And John A. Smith III, an assistant U.S. attorney representing the government, said that similar efforts to survey land along the border have met little opposition from ranchers and other private landowners.

But the church wants to keep authorities from even stepping onto the chapel grounds.

“This is the small fight before the big fight,” said Daniel Garza, a Brownsville lawyer representing the diocese. “Most people don’t fight the little fight, but we don’t believe in having anything related to a wall on our property, period.”

"Respite and worship, accessible to all"

La Lomita was first established as a halfway point for members of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a sect founded in the 1800s that focused on marginalized or remote communities, said Friar Bob Wright, a professor at the Oblate School of Theology in San Antonio who has researched the group’s presence in Texas.

Snipes calls the Oblates, who would ride around the area on horseback, the original "cowboy priests."

After an original chapel on the land was destroyed in a flood, the current building was erected in 1899 and served as the headquarters for missionary activity in Hidalgo County. The town of Mission got its name and its emblem from the chapel.

“The mission became a place of worship and local devotion,” Wright said. “It’s historical for the whole Middle Valley community, one of the earliest sites there, and for the religious community, too.”

That importance has led the Oblate’s leadership in Illinois to issue a strong rebuke against federal control over the chapel.

“It has been and remains a true place of ‘sanctuary’ in every sense of that term — a place for safety, respite and worship, accessible to all, giving peace and security in human and spiritual form,” the Very Rev. Louis Studer, the group’s U.S. provincial, said in a statement.

Just one year of surveying and inspection could cause “significant damage” to the park around the chapel, where parishioners regularly come to pray and host an annual mariachi mass, Garza said. The chapel has also been home to weddings, private confessions and the occasional retreat for priests in the Guadalupe parish.

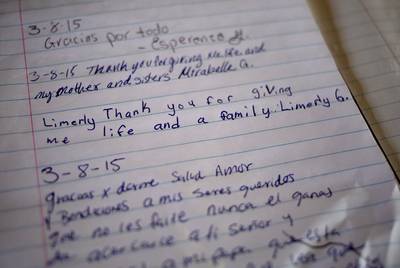

Many of these notes ask, or give thanks, for miracles. Miguel Gutierrez Jr

What might come after that could be more severe.

“You’d have the wall, and you’d have this 150-foot enforcement zone basically right against the church,” Garza said. “They’d have to knock down some of the beautiful trees that have been there forever. You’d go from a green area to a gravel road."

The church's main legal argument in court rests on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which Garza says requires authorities to demonstrate a “compelling interest” to obstruct local Catholics from practicing their religion at La Lomita.

Snipes fears that even if authorities installed a gate to access the chapel if a wall is built nearby, parishioners would have to check in with Border Patrol every time they wanted to stop by.

“What happens to the altar boys who are all dark-eyed and dark-skinned?" he said. "Who goes down to the chapel to pray with papers?”

Devotion and cariño

Among La Lomita's most devoted parishioners is 82-year-old Andrea Chavez Garza, who travels to the chapel nearly every day in spite of a crippling arthritis that has limited her mobility since birth.

Inside the peeling white walls of La Lomita, Chavez prays the rosary and recites sermons that she learned by heart as a toddler when her abuela would take her there to pray.

“If I don’t go to the chapel, the day’s not complete," she said. "That’s how I was raised. So for them to get rid of this beautiful, historic space? Over my dead body.”

was destroyed in a flood and the current building was erected in 1899. Miguel Gutierrez Jr

At times, those seeking out the chapel have been border-crossers themselves.

Snipes, the "cowboy priest," said he found three Central American migrants hiding out in the chapel last fall. He snuck them bread and soup as they stayed inside.

He could have ignored their pleas for help. But it's all part of his own mission, he said, to bring charity and humility back to the priesthood and carry on the Oblate tradition — the same force that compels him to stand against the wall, and in recent weeks, to lead mass at La Lomita every Friday before dawn to pray for the chapel's protection.

"We're obsessed with correctness instead of cariño," he said, using the Spanish word for affection. "And cariño is what people are dying for."

Read related Tribune coverage

- Federal officials unveil plans for four-mile, 18-foot-tall wall on Texas-Mexico border

- Texas Parks and Wildlife: State park could close if Trump builds border wall through it

- Trump’s border wall threatens to end Texas families’ 250 years of ranching on Rio Grande

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2018/12/19/church-and-state-fight-mission-texas-border-wall/.

Texas Tribune mission statement

The Texas Tribune is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.