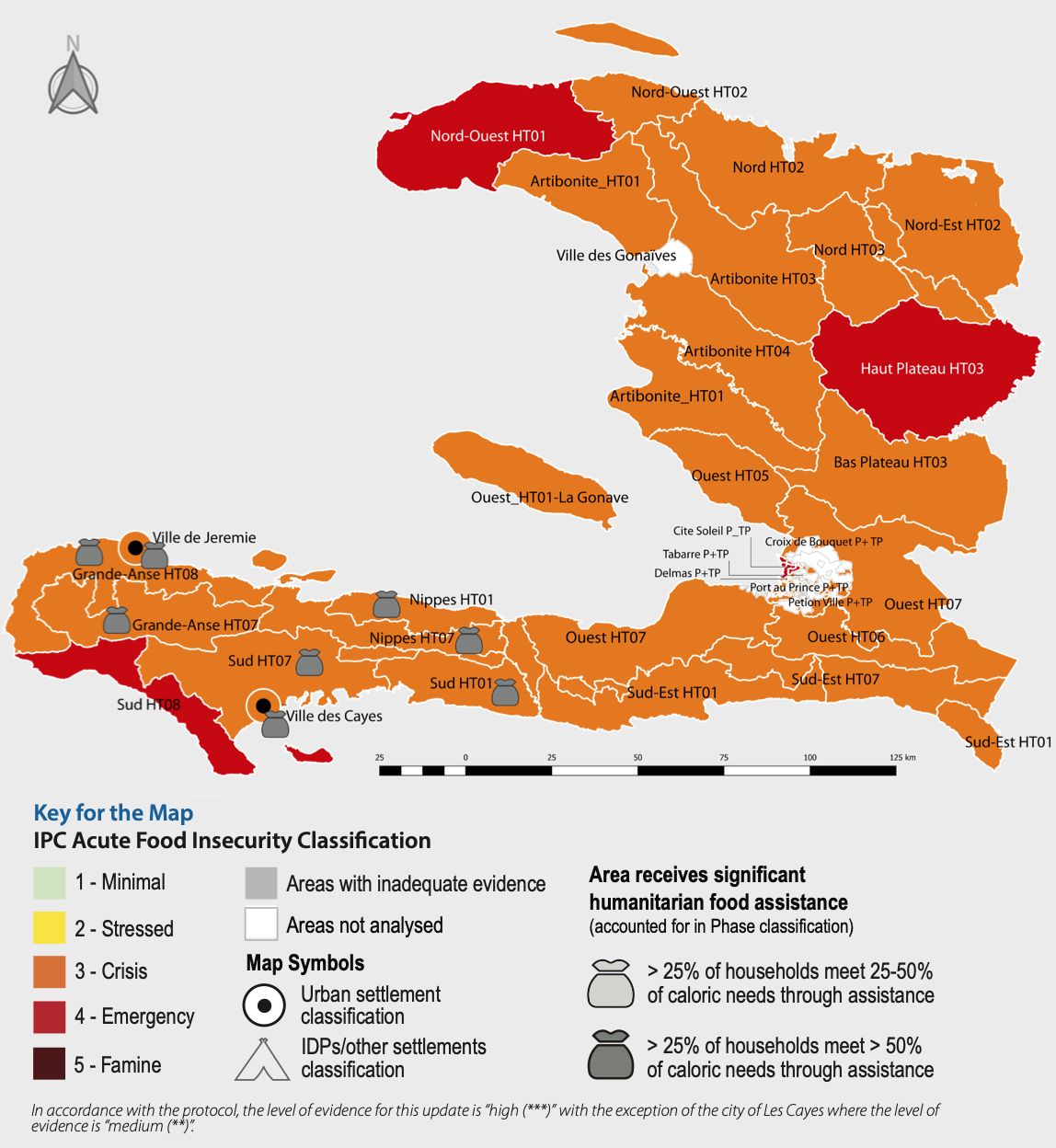

[caption id="attachment_10420" align="alignright" width="500"] Integrated Food Security Phase Classification Snapshot | March - June 2022 (Projection update)[/caption]

Integrated Food Security Phase Classification Snapshot | March - June 2022 (Projection update)[/caption]

At least 4.5 million people in Haiti, or 45% of the population, are facing acute hunger. As the war in Ukraine drags on, the number is certain to go up. Prices for food are spiking everywhere, with the cost of fuel adding to the pain. The immediate crisis in Haiti is thus symptomatic of global stressors largely outside the control of the people of the country. From a longer term point of view, the food crisis in Haiti has deep roots in years of exploitation.

For many US Americans, the New York Times recent series of articles on Haiti was their first encounter with this history of exploitation. The centerpiece of the Times' analysis was a discussion of the so-called “independence debt” demanded by the French government, some twenty years after Haiti won its independence in 1804. In 1825, the French government demanded 150 million francs as an indemnity to recompense property owners, including those who previously “owned” enslaved Haitians, who lost their holdings as a result of the revolution. Under threat of a naval bombardment by French warships, Haiti's president agreed to pay.

Haiti could only pay this ransom by borrowing from French banks at usurious interest rates, creating a “double debt.” The authors of the Times' series argue that paying off this debt cost Haiti the equivalent $21 billion over the years, money that might have otherwise gone to infrastructure and the financing of local industry. Indeed, the independence debt was not paid off until 1947. The final installments were not to French banks, but to the National City Bank of New York, the predecessor to CitiGroup, which had assumed the remaining portion of Haiti's “double debt.” It also assumed control of Haiti's national bank, in a process that began in 1909 and culminated during the US occupation of Haiti (1915-1934).

Global pillage

As the New York Times shows, Haiti's current troubles have grown in the context of these fertile fields of exploitation. It is the uncomfortable truth that the wealth of European and US American financiers today derives in no small part from the historic impoverishment of Haiti, and the Caribbean more generally. Indeed, the entire edifice of 19th century imperialism still casts a long shadow over the poverty of countries throughout the global south. Haiti's story is unique in the degree of exploitation; it has been the cost imposed on Haitians as the result of a successful social revolution led by enslaved peoples, the only such revolution in history. However, Haiti's story is part of a global tale of ongoing theft.

To this day, countries of the global south transfer more wealth to the global north in the form of profit repatriations, tax evasion, unequal exchanges from labor exploitation, debt repayments and historic trade imbalances, than flows the other way in the form of direct investment, “aid” and new lending. It's not even close. Studies have shown repeatedly the net resource transfers from “developing” to “developed” countries recently comes to $2 trillion a year. One study, published in New Political Economy last year, concluded that the “drain from the South remains a significant feature of the world economy in the post-colonial era; rich countries continue to rely on imperial forms of appropriation to sustain their high levels of income and consumption.” The scale of the plunder is extraordinary. From 1960 to 2018, they found, the “drain from the South totalled $62 trillion (constant 2011 dollars), or $152 trillion when accounting for lost growth.”

Debt and the destruction of Haitian agriculture

What do these global and historic trends mean in concrete terms for Haiti today? People are hungry, the government can no longer govern, and gangs are profligate.

Sandra Wisner's recently published study, Starved for Justice: International Complicity in Systematic Violations of the Right to Food in Haiti outlines in detail the role of USAID, and international financial institutions such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, in enforcing policy prescriptions on Haiti that devastated local food production. These policies are a continuation of the patterns of exploitation set in place in 1825, but with the United States, not France, as the primary perpetrator.

The story of rice is the best known example, although not the only one. “[I]n 1985, Haiti produced 163,296 tons of rice and less than 5% (7,337 tons) of all rice consumed was imported from the United States. But in the last decade alone, Haiti's rice imports have increased by nearly 150 million metric tons. In 2020, Haiti imported almost $245 million worth of United States produced rice, making the country the third largest market for North American rice after Japan and Mexico.”

This change from consumption of Haitian rice to US imported rice was facilitated by a reduction in tariffs for rice, from 50% to 3% in 1994. The lowering of agricultural tariffs was part of a bundle of reforms that also included cuts to public sector spending, including slashing support credits for rural farmers, and adopting a floating exchange rate. All of these reforms were mandated by international financial institutions as part of structural adjustment programs, which were in turn imposed on Haiti to facilitate the payment of debts to international creditors.

Urbanization

Between 1986 and today, Haiti's economy and resulting social relations have been utterly transformed by the decline of agricultural production. In the waning years of the Duvalier dictatorship, Haiti's population remained largely a rural one. Twenty-four percent of Haiti's population, representing 1.56 million people, lived in cities in 1986. Today, the percentage is 57% of the population, or 6.55 million people, who live in cities.

This quadrupling of the urban population in just 36 years has been wholly unsustainable. Indeed, the consequences of insecure housing, lack of services, and impoverishment became quite clear when Port au Prince was struck by an earthquake in 2010. Public health scholar, Jean Carmalt, wrote, “When the earthquake struck on January 12, 2010, there were approximately 2.7 million people living in the city, with an additional 75,000 new migrants arriving in the city every year. About 85% of those migrants moved into informal or illegal settlements.” An estimated 300,000 people died in the earthquake, an unprecedented toll clearly driven by overcrowding and insecure housing. Despite the evident stress on the city's capacity to support the population then, there are nearly 700,000 more people living in the metro area today than in 2011. This overcrowding is in large part a result of the ongoing devastation of the rural economy.

Formal employment in Haiti (jobs with set wages or a salary) was about 11.5% of the working age population (15 years +) in 2016, with total employment for the same age group at 68%. This means a third of the population over 15 years of age is without work, and the vast majority of the people with jobs are in highly insecure situations in the informal economy. A clear outgrowth of rapid urbanization coupled with such low employment opportunities has been the explosive formation of criminal gangs over the last 20 years and their alliances with competing political and economic elites. These gangs now control large swaths of the country, including major transportation routes in and out of Port au Prince.

Employment rates in rural areas are even lower. People with land are wholly dependent on what they can grow and get to market to survive. For others living in small rural communities, they either find what work they can on local farms, or migrate to cities. The opportunities are, in either case, slim. It is not surprising that gangs have now expanded into rural communities as well. In one case, a gang in the extended “family” of the notorious 400 Mawozo gang based in Croix des Bouquet, took over several small villages north of Pandou. Families displaced by the gang actually have to pay “tax” now in order to return and tend their farms during the day.

None of this is the result of “natural” market forces. Rather, the crisis is the result of specific policies imposed on the country that maintain historic forms of pillage. The New York Times series helps us understand how much of this started; but we should all understand that it is ongoing.

Food security requires food sovereignty

Moving into summer this year, with gas prices soaring, and a devalued exchange rate eating away at people's purchasing power, hunger is widespread in Haiti. Every section of the country is facing at least “crisis” levels of food insecurity, with several departments moving into emergency levels, including the West department (Port au Prince). The World Food Program is estimating 1.3 million people are in need of urgent food assistance.

The playbook for such a crisis tends to have a short term view. Food is brought in from the United States, and either given away, or monetized at levels that undercut local food production. Food aid has long been a means for large US-based agricultural producers to offload surplus production at a profit; e.g. they sell it to the USDA's Commodity Credit Corporation, which then transfers the food as “aid” to the World Food Program, or non-governmental organizations like Catholic Relief Services.

A result is that a short-term solution to the looming food crisis in Haiti runs the risk of becoming part of the longer-term problem of declining food production, dependence on imported food and the ancillary effects of all of this on society.

At this point it is tempting to point to “the solution.” That would be more than a bit presumptuous. Yet, any solution to the crisis of food insecurity clearly requires supporting the revitalization of agriculture, and in ways that augment food production. If Haiti is to become food secure, it must become food sovereign.

Any expansion of production must be done with longer term sustainability in mind, employing a mix of reforestation, food produce, and animal husbandry such that soils can be replenished, and local rain patterns can return to a semblance of predictability. Tariffs would have to be reset at levels that offset dumping of agricultural products from the United States and elsewhere.

Before any of this can happen at a scale necessary to turn the crisis around, public policy in Haiti must be reoriented toward protecting Haiti's long-term interests, not the interests of transnational banks, US corporations or non-governmental organizations. In the medium term, however, we can support programs that build up local capacity for food production in sustainable ways.

This is the work of our partners at the Jean Marie Vincent Formation Center, where the staff coordinate with small farmer associations to organize educational programs and provide direct material support for projects that boost local productive capacity. They work with farmers throughout the process of planting, tending, harvesting and marketing their produce in all eight communal sections of Gros Morne. Scaling up such programs is a priority for our work in Haiti.

We must also continue to press the United States government to change its policies. The United States government exercises an oversized degree of control in Haiti, and does not do so with the interests of the majority of Haitians in mind. Haiti is still struggling for its independence, and we, in the United States, are part of the problem. We can do better. We must do better.