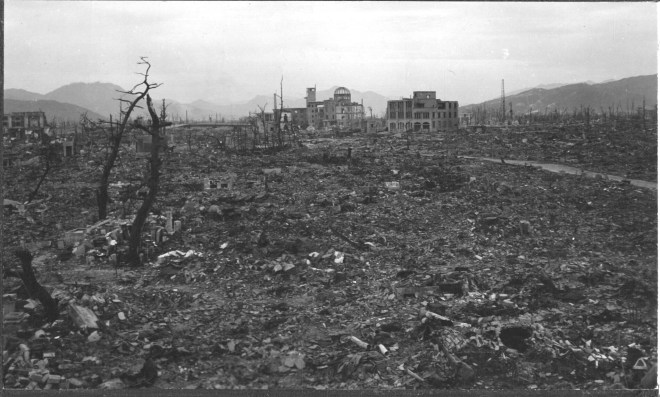

Over a three day period, the United States government authorized the murder of 200,000 civilians with the dubious claim that doing so saved lives. And despite the horrors unfolding, the intent was to keep dropping the bombs - another raid was planned for August 18. Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945.

In Japan, the survivors of the atomic bombings are called hibakusha. For decades there was a real stigma in being hibakusha. People feared that radiation sickness might be contagious, or that the effects could be passed down through generations. Allied, mostly U.S. forces, which occupied Japan until 1952, helped generate the silence surrounding the bombings and their survivors.

The Allied forces, led by the US Occupying force, General McArthur, had censored all information, including the scientific and literary publications about the bombings – for instance film reels were confiscated, along with scientific specimens and doctors’ records. These were then shipped off to the US. The hibakusha, who were examined medically, for the famous Life Span study (the longest study of radiation effects in existence) were, in general, not interviewed for their experiences, except for a very few psychological studies.

Instead, the hibakusha were the unwelcome reminder of an unknown, unclassifiable event, something so unimaginable society tried to ignore it.

In 1957, a law was passed so that those hibakusha who had illnesses that could be traced back to the bombing were able to receive medical stipends to pay for their care. (For some years, the government failed to recognize as hibakusha non-Japanese survivors, especially thousands of Koreans who had been brought to Japan as laborers during the war and then died in — or survived — the bombings.) Even so, it has only been in the last decade or so that the stigma of being hibakusha has lifted. Of the 650,000 people who survived these bombings, 120,000 were still alive in 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bcmub5rz3Zc

A nijū hibakusha refers to someone who survived both bombings. While as many as 165 people have been identified as nijū hibakusha, the only person to be officially recognized as such by the government of Japan is Tsutomu Yamaguchi. From Nagasaki, Yamaguchi was in Hiroshima on a business trip for Mitsibushi on the morning of August 6:

At around 8:15 am...Yamaguchi heard a plane circling above the city, and then saw something drop from it. Two small parachutes were visible in the distance, carrying a big object that was slowly making its way towards the ground in the center of the city. Yamaguchi was about 3 km away when suddenly a blinding flash of light went off. The explosion aggressively pushed Yamaguchi back and severely burnt the left side of his upper body. Confused and in pain, with ruptured eardrums and temporarily blind, he managed to crawl into an irrigation ditch before making his way into a shelter for the night.

Yamaguchi returned to Nagasaki on August 8. With just bandages as treatment for his wounds, he was back at work at his office in Nagasaki the next morning. While explaining what he saw in Hiroshima to his boss, who was doubtful a single bomb could do such damage, the second bomb struck. Yamaguchi survived the second bombing - as did his wife and young son.

In 2010, the year Yamaguchi died of stomach cancer, a book of his poetry was published in English for the first time. The book, titled, “And the River Flowed as a Raft of Corpses,” contains 65 poems translated by Chad Diehl. The poems are "tankas," a poetry form, which like haiku, has a specific rhythmic structure (which constrains translation). On surviving:

Carbonized bodies face-down in the nuclear wasteland

all the Buddhas died,

and never heard what killed them.

Thinking of myself as a phoenix,

cling on until now.

But how painful they have been,

those twenty-four years past.

If there exists a GOD who protects

nuclear-free eternal peace

the blue earth won't perish.

World War II was not a “great” war. It was a global travesty involving the slaughter of tens of millions of people in the name of “great powers” competing for global position. That such a war ended in tragedy is somehow fitting. The atomic bombings provided the segue between the old global order of European imperialism and the new, U.S. imperialism launched under the reign of terror that is the threat of nuclear annihilation. We still live under the shadow of the bomb. And so, we must remember the source, and all the brutality associated with those bright lights in the morning skies above Japan in August of 1945, and vow "never again."