On Sunday, October 2, acting health officials announced that 8 people had died of cholera in the community of Dekayet in southern Port-au-Prince and in Cite Soleil. These are the first cholera cases in three years. Prior to 2010 Haiti had no recorded cholera cases. That changed when at least 10,000 people died from cholera in Haiti following an outbreak in 2010. Soldiers from Nepal, who were present as part of the UN mission (MINUSTAH), caused the outbreak. Raw sewage from their camp drained into the Meille River, the principal source of drinking water for nearby communities. The UN refused to admit any direct responsibility for six years, and has still failed to fully respond.

Ryot Films released a short documentary called Baseball in the Time of Cholera a couple of years after the outbreak began. The documentary tells the story of one family impacted by cholera against the backdrop of the UN's obfuscation of its responsibility. One cannot really quantify pain, of course, but it is not impossible to imagine 10,000 funeral scenes like the one depicted in the documentary; a glimpse of how trauma caused by the UN’s indifference was rendered in the life stories of a generation of Haitians.

In establishing MINUSTAH, the United Nations took over the occupation of Haiti in 2004 from a military force composed of troops mostly from the United States. Those troops had coordinated the removal of President Aristide from the country that February. The UN mission was to “stabilize” Haiti in the wake of the regime change. The mission was a massive failure.

MINUSTAH was a peacekeeping mission mobilized in the absence of an actual war, yet remained in Haiti until 2017. Brazil led the military component of MINUSTAH, launched during Lula’s presidency (2003-2011). Human rights violations were rampant throughout MINUSTAH’s occupation, most notably in 2005 and 2006 when military raids in Cite Soleil and other popular neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince killed dozens of people. The Brazilian military acted with absolute impunity.

MINUSTAH shut down in 2017, replaced by the United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti (MINUJUSTH). MINUJUSTH is a vehicle for continuing the training of Haiti’s National Police (HNP), among other tasks. The UN occupation of Haiti created the HNP, paid for and trained in cooperation with the United States. Their track record is not good.

MINUJUSTH trainers were present in the fall of 2017 when Jimmy Cherizier, then an officer in the HNP, organized a massacre at a school in Grand Ravine, killing nine people over the course of several hours. UN forces were blocks away and did nothing. MINUJUSTH officials took no responsibility, claiming they were not physically on the campus at the time of the killings and thus not responsible; there was little investigation, and no accountability.

The following year Cherizier was part of another massacre in La Saline. On November 13, 2018: “[t]he perpetrators began firing automatic weapons around 4pm, and over the course of fourteen hours, killed at least 71 residents, including children and a ten-month-old infant. Some of the perpetrators wore [police] uniforms and lured residents out of their homes under the guise of a [HNP] operation, then executed them in the streets.” Following tremendous pressure from human rights groups inside and outside of Haiti, there was an investigation that identified Cherizier, among many others, as involved in the killing. By the time this investigation occurred, however, Cherizier had already been implicated in another massacre in Bel Air.

After the investigation, Cherizier left the police force, but he has never been prosecuted or seriously threatened with arrest.

Cherizier now oversees the largest federation of armed groups in Port-au-Prince, the G9 Family and Allies. The G9 has gone to war with other armed groups repeatedly since 2020, leading to hundreds of deaths in Port-au-Prince and outlying areas. Thousands of people have been internally displaced by the violence. Thousands of Haitians are also leaving the country.

Currently the G9 is in control of the fuel terminal at Varreux. As a result of this blockade of gas, diesel and kerosene supplies, hospitals are unable to operate at full capacity. Water trucks are unable to run. Schools, scheduled to open this week after some delay, are not opening. People are starving.

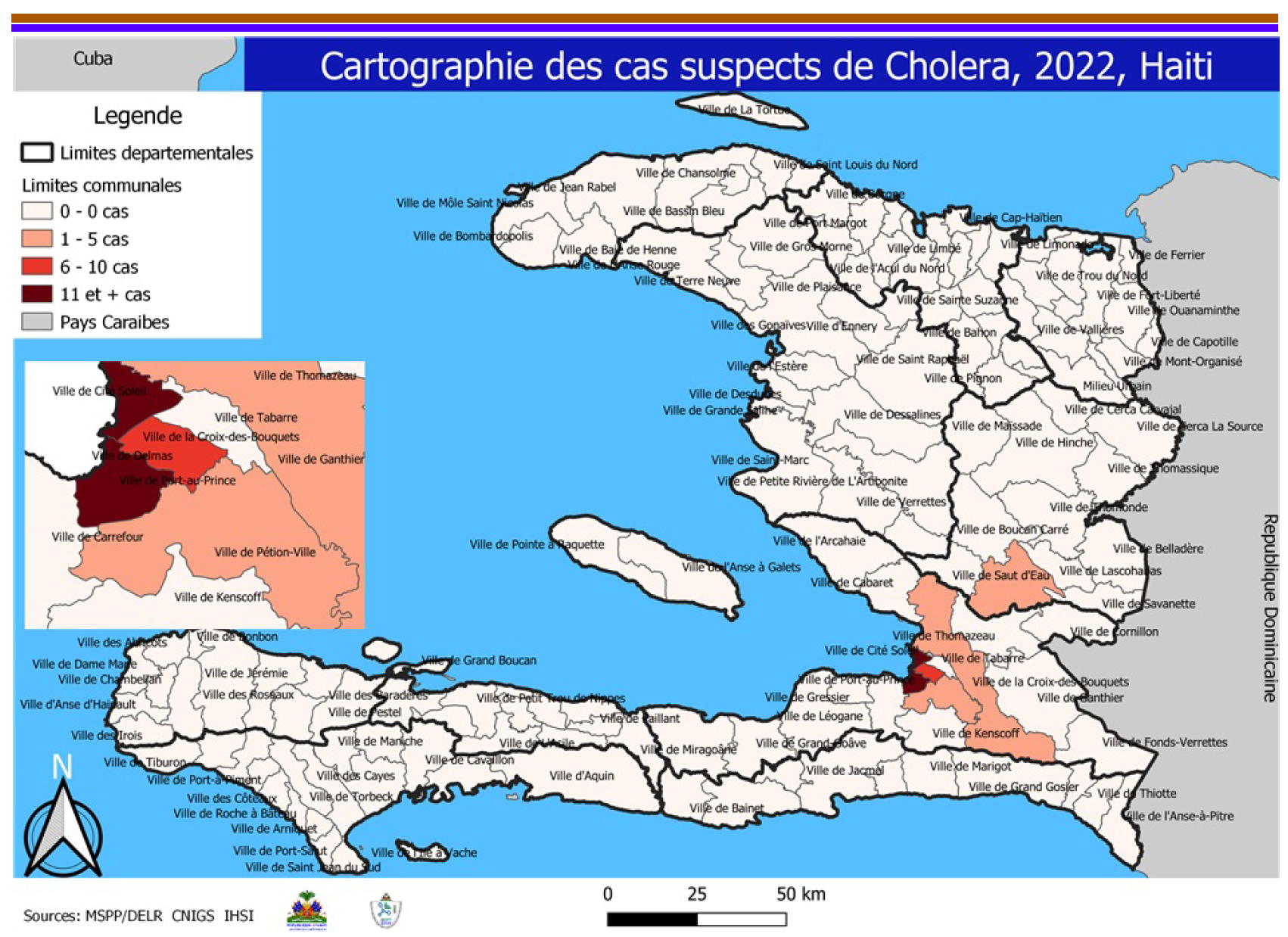

And now, cholera is resurgent. There are limited clean water supplies. Supply chains for basic medical supplies are in tatters. There is no fuel to operate the generators needed to provide medical care at most hospitals. Household solutions are also limited. The fuel needed to boil water, for example, is not available. Propane cannot be found, and even charcoal supplies in the cities are scant. The prospect of a severe cholera outbreak is looming large. At least 111 more suspected cases have been noted by health officials.

The spread of cholera follows the same trail as the bloodletting of the gangs. Both lead back to recent United Nations’ missions, and, through them, a long line of foreign interventions that have treated the majority of Haitians as a containment problem.