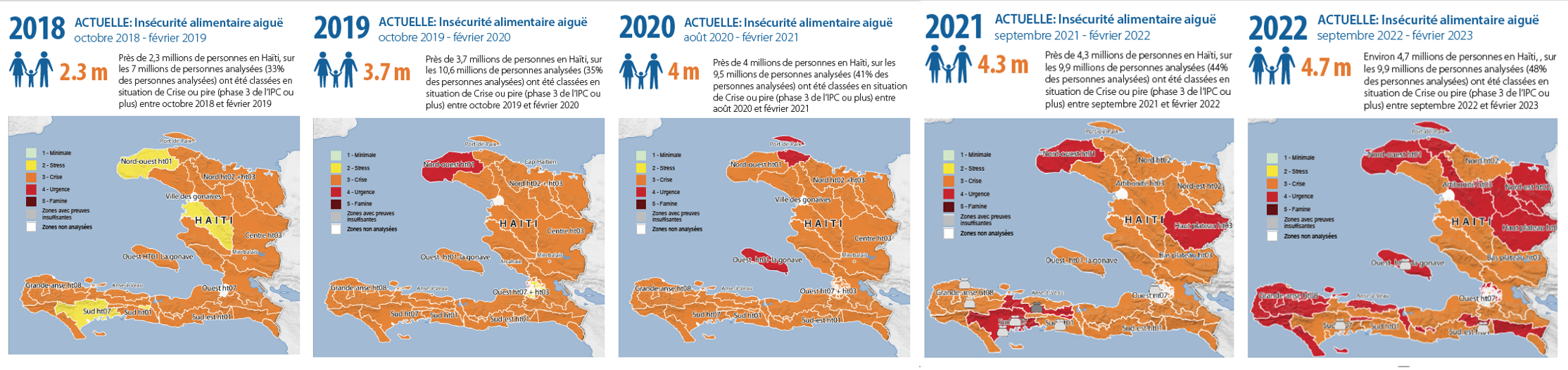

A portion of Haiti’s population is experiencing famine conditions for the first time since the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) system was created in 2004. 19,000 people in Cite Soleil are estimated to be at risk of starvation. Outside of Port-au-Prince, the situation is also dire. IPC estimated 4.7 million people are facing severe food insecurity, with 1.8 million people at “urgent” levels.

The immediate trigger for famine conditions in Cite Soleil is the ongoing influence of armed groups, with gang warfare in Port-au-Prince neighborhoods, including Cite Soleil, going on for months now. However, if one compares maps over the last five years, there is a clear pattern of food insecurity worsening each year.

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) was established in 2004 to track famine in Somalia. The system has been expanded, and is now used by UN agencies, individual governments and others to track food security in countries around the globe. The IPC system uses five levels of increasing insecurity: minimal, stress, crisis, urgent, and famine.

What the classifications mean

The charts above show that 4.7 million Haitians are currently facing crisis levels of food insecurity or worse. At the “crisis” level, there are either gaps in people’s food consumption sufficient to contribute to heightened levels of malnutrition, or people can only feed themselves by foregoing other necessities. According to the IPC system, 2.8 million Haitians are in this situation.

At the “urgent” level, food gaps are so severe that people are suffering from acute malnutrition, sufficient to cause an increase in excess mortality, or, they can only feed themselves by “employing emergency livelihood strategies and asset liquidation.” This is the situation currently faced by 1.9 million Haitians. The looting of food supplies stored by humanitarian agencies over the past month was one response to this level of insecurity.

Finally, 19,000 people in Cite Soleil are now at famine levels of insecurity. Cite Soleil is a large, highly populated area of Port-au-Prince that sits on low lying land adjacent to the Varreux fuel terminal and other port facilities. It has been the site of gang warfare over the last several months, and is now under the control of the armed group known as the G-9 Federation. The gang is using this position to blockade the Varreux terminal, which stores 70% of Haiti’s fuel.

The resulting lack of fuel around the country has had an enormous impact on food security, as transportation has come to a halt and prices have skyrocketed. This threatens to push more people from crisis to emergency levels of insecurity, and others from emergency to famine levels.

The events of the last 6 weeks, when the blockade at Varreux began, are not the cause of food insecurity. The issues run deep. Back in June we discussed the historical evolution of food insecurity as a consequence of the reliance on food imports, itself a byproduct of historical political formations and processes within Haiti, and between Haiti and external powers.

A response: Food Sovereignty

The Smallholder Farmers Alliance has published a series of articles addressing food insecurity as the result of Haiti’s loss of its “food sovereignty.” Haitians used to produce most of the food needed to feed the country. Indeed, just 40 years ago, the magnitude of the hunger the country is now facing would have been unthinkable. Unless Haiti can recreate food systems that are locally sourced, the situation is likely to continue to get worse. And food insecurity is a major underlying cause of the political crisis and violence engulfing Haiti as we write this.

Supporting and building out local food systems is the primary reason for our partnership with the Jean Marie VIncent Formation Center, located in Grepen just outside of Gros Morne. Back in 2020, members of the Grepen team took part in a survey organized by the Smallholder Farmers Alliance. The survey asked farmers, and those who work most closely with them, what they need to enhance local food systems. The results were published last year, and offer a road map of work closely aligned with the work we support through the Jean Marie Vincent Formation Center. Their recommendations:

-

Local Seed Sourcing: Food sovereignty starts with smallholders owning and managing the source of their own open-pollinated, non-hybrid and non-GMO seed in the form of ‘seed banks’.

-

Local Food Purchasing: Having the World Food Programme and other providers of school meals and emergency food purchase more locally is a start, but they are handicapped by their own donor restrictions.

-

Invest in Regenerative Agriculture: While not yet a household name, regenerative agriculture is emerging as the new global gold standard for sustainable farming, [focused on different techniques to regenerate topsoil]. Haiti is already involved and could take on an even greater role.

-

Working for Gender Equity: Providing micro loans to women farmers is one of the SFA’s most successful programs and has lessons for improving agriculture through gender equity.

-

Fix the U.S. Farm Bill: This U.S. legislation places arcane restrictions on USAID when establishing programs to improve smallholder farming in Haiti and other countries.

While the immediate crisis facing Haiti is dire, and calls for immediate action understandable, there is no short term solution to food insecurity. Addressing the systemic issues underlying this crisis, which has been devolving for years with scant attention from the international community, requires a longer term vision.

That vision already exists among Haiti’s small farmers. It involves localized solutions, like those outlined above. We offer our support by investing in this vision. In solidarity, we also work to push the U.S. government, historically a major obstacle to reform in Haiti, to do things differently.

Comments

Kim Hart (not verified)

From my understanding, Haiti used to have a stronger agriculture. In the 90's the U.S. used policies to have Haiti import so farming was not as lucrative. Many Haitians moved from rural to urban areas at that time. Now it is a challenge to convince young people to go into farming. Young people have commented that living in rural locations and farming are not enticing as there are no urban amenities. Farming is a profession with dignity and is the foundation for local food systems. I believe the recommendations listed above are solid. The key is sustainability. In my work, on a much smaller level in Haiti, I have seen first-hand how smart, entrepreneurial and business-saavy Haitian women are in running their micro-loan businesses. Many were single mothers who had the sole responsibility of feeding and raising their children. I am excited to read the recommendation of Working for Gender Equity and looking for localized solutions.