Between October 1, 2021 and April 30, 2022, the US Border Patrol encountered a number equivalent to 1 out of every 69 Nicaraguans trying to get into the United States - a higher portion relative to population than any other country in Central America this year. “Encounter” refers to someone apprehended for attempting to enter the United States in an unauthorized manner, or deemed inadmissible at a port of entry, or anyone expelled under Title 42 authority.

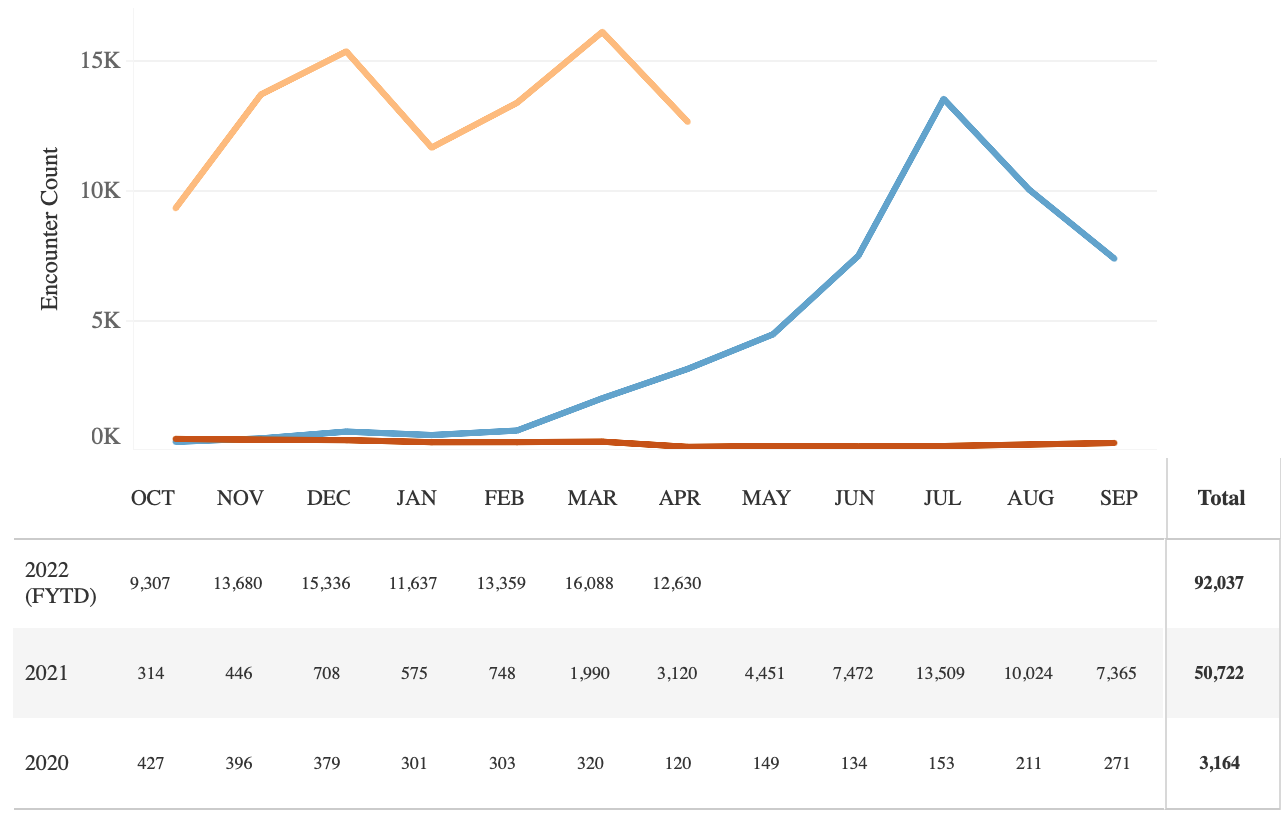

[caption id="attachment_10402" align="aligncenter" width="800"] Border Patrol Encounters Nicaragua[/caption]

Border Patrol Encounters Nicaragua[/caption]

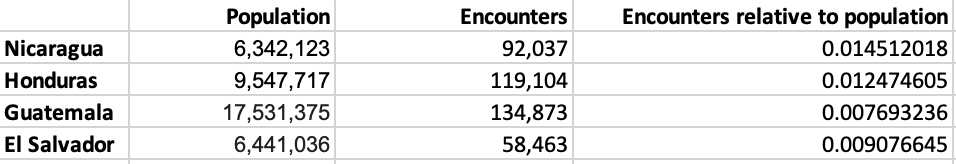

The number of Border Patrol encounters with people from Nicaragua stands at 92,037 this fiscal year (between Oct 1 and April 30). The total for all of FY 2021 was 50,722. There were only 3,164 encounters from Nicaragua in FY 2020. Adjusted relative to population, the number of people from Nicaragua the US Border Patrol has encountered so far this year represents the largest group from Central America. [Encounters as a percent of population in FY 2022 = 1.45% for Nicaragua, 1.124% for Honduras, 0.76% for Guatemala, and 0.90% for El Salvador.]*

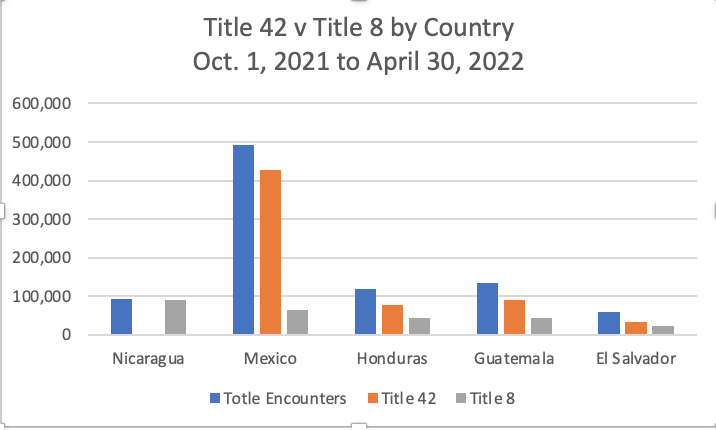

For anyone trying to get into the United States, Border Patrol processes them under either Title 8 or Title 42 authorities. Title 42 refers to an order issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that permitted the Trump and Biden administrations to summarily expel anyone encountered by Border Patrol. This order effectively denies asylum to anyone crossing between ports of entry, and also denies asylum and other humanitarian relief at ports of entry.

When Title 42 first went into effect in March of 2020, Mexico refused to accept people being expelled unless they were Mexican nationals, or from Guatemala, El Salvador, or Honduras. As a result most Nicaraguans were processed under Title 8. Title 8 simply means they are processed under “normal” (pre-Title 42) authority.

Entering under Title 8 authority does not mean Nicaraguans will get to stay. Most will be detained, or enrolled in an ankle monitoring program, while they await hearings, and most of them will eventually be deported. For example, of all Nicaraguan asylum claims processed from 2001 to 2021, an average of 29% were granted. In recent years the percentage of approvals is up, but the total number of cases is way down as immigration courts are seriously backlogged. In FY 2021, the US granted 43% of asylum claims from Nicaragua, but the total number of cases considered was 446.

Many people seeking asylum from Nicaragua are also redirected to wait in Mexico. Nicaraguans make up 73% of enrollments in the revamped Migrant Protection Protocol (“Remain in Mexico”). Processing under Title 8 authority has never been easy, and this has certainly not changed for the better during COVID. Indeed, in preparation for the possible end of Title 42, the Biden administration is looking to expand expedited removal, and give “credible fear” screening authority to agents at the border, which does not bode well for people trying to stay in the country no matter where they are from. Finally, the Biden administration recently negotiated an agreement with Mexico to accept Nicaraguans expelled under Title 42. The current agreement is limited in scope; it totals about 60 people a day (which still adds up to 1,800 people a month). This could expand depending on what the courts ultimately decide about Title 42's future.

Some reason why

So, for the first time in many, many years, an increase in migration from Nicaragua to the United States is outpacing other countries in Central America relative to population - in absolute terms, the number of people from Nicaragua has already surpassed El Salvador and is not far behind Honduras and Guatemala. There is no single reason, of course. And it is difficult to assign a weight to various causes. But we can discuss what some of the factors are, and what might be unique in the case of Nicaragua versus other countries in Central America.

Political instability in Nicaragua is the only reason ever given much weight in US media accounts of Nicaraguan migration. While this is certainly a part of the reason for the increase, it is very far from the whole story. Indeed, political instability is hardly a factor unique to Nicaragua. Political repression and social violence is still far worse in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. If Nicaragua is outpacing its neighbors in migration right now, it is not due to more political instability.

Economic stress from COVID-19 is no doubt part of the equation, as it is for much of Latin America. Indeed, Border Patrol encounters are up across the board, to the highest levels in 20 years. That said, while Nicaragua has been battered like the rest of the region, its economy is in recovery. So, economic retraction from COVID would not be worse for Nicaraguans than the rest of Central America - though sanctions complicate this picture.

The factors that are unique to Nicaragua viz other countries in Central America are: 1) US sanctions; 2) the decline in opportunities for seasonal migration to Costa Rica; 3) as noted above, the fact that until April of this year, Nicaraguans have mostly been de facto exempted from Title 42 at the US border.

US sanctions against Nicaragua have taken two forms: individual sanctions against members of the government and their families; and generalized sanctions in the form of restrictions placed on multilateral loans. Forty-one people have been sanctioned by the US Treasury Department in Nicaragua. It is difficult to know what impact this has on the economy, but certainly many of the people involved are in positions of authority in government, which would disqualify them from joint ventures with US based business interests. Generalized sanctions hit at the same time as COVID-19. The World Bank issued no new loans to Nicaragua between March of 2018 and November of 2020, and the IDB offered few new loans until a COVID support program of $43 million in the summer of 2020 - compare that to $1.8 billion in new lending to El Salvador during the first 7 months of 2020, including $300 million to address COVID.

The easing of some multilateral lending on humanitarian grounds after hurricanes struck Central America in November of 2020 led the United States to impose further monitoring on these loans, a provision included in a new round of sanctions called the Renacer Act passed in November last year. Renacer also directs the Biden administration to investigate the removal of Nicaragua from the Central American Free Trade Agreement. Whether or not the United States would impose trade sanctions at this level (or even if it can take such unilateral action) the discussion of such an outcome might chill investment.

What all of this has meant for Nicaragua's economy and employment is hard to disaggregate from the overall chilling effect of COVID-19. In recent months the country has seen growth in the economy. Would this recovery be more robust absent sanctions? Probably. Certainly sanctions have not helped. What we can say with some certainty, however, is that from the standpoint of US policy, sanctions have backfired, having likely contributed to an increase in immigration, and led to Nicaragua's re-engagement with China, which was announced by Nicaragua shortly after the signing into law of the Renacer Act. Meanwhile, Ortega shows no signs of going anywhere. Calls for even more sanctions in response seem quite short-sighted.

When I wrote about migration from Nicaragua last October, an important dynamic in the increase in people heading north was the decline in people heading south - to Costa Rica. In 2020 and 2021 net migration of Nicaraguans to Costa Rica was negative. The reduction was stark, from 800,000+ border crossing annually pre-COVID, to just 270,000 in 2020, with 143,000 Nicaraguans returning to Nicaragua, vs 130,000 traveling to Costa Rica. From August 2020 to September of 2021 the number of crossing was down to 170,000, again with more Nicaraguans returning to Nicaragua than traveling to Costa Rica. In short, Costa Rica's economic woes have largely closed off the economy to Nicaraguans migrating there for seasonal work, and the decline in opportunity in Costa Rica, has as its corollary, more migration toward the United States.

The impact of Nicaraguans being left out of Title 42 expulsions is harder to know. Anecdotally, I have heard from a number of people in Nicaragua that the word on the street is Nicaraguans are “getting in” to the United States. People migrating are also coming from all walks of life, and all political affiliations - it is not just the poor, and certainly not only people from opposition neighborhoods. There seems to be a general understanding that Nicaraguans will have an easier time at the border than other Central Americans, and that may be a factor in encouraging more people to try and migrate. As noted above, however, nothing is easy here. The Biden administration has already looked to increase expulsions of Nicaraguans to Mexico, and if Title 42 remains the policy, as it appears it will for the next few months, those numbers may increase.

It is difficult to draw firm conclusions about which factors weigh most heavily. Economic stress seems to be a major part of the big picture here (impacts of COVID-19, sanctions, employment issues) as they are for most of the region, even as a rough recovery is underway. Certainly some of the increase is people seeking asylum from ongoing political conflict. The United States government should reconsider its policy of sanctions - which has thus far only exacerbated tensions. Turning Nicaragua into a meso-American version of Venezuela by levying more and more sanctions, including trade restrictions as some have advocated, would be a disaster. Finally, US border policy remains an inchoate mess - leading to misinformation and much confusion. For Nicaraguans, and everybody else at our border, creating a humane, sensible process for screening and evaluation is what is needed.

*Figures below