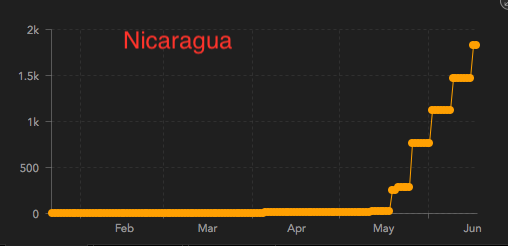

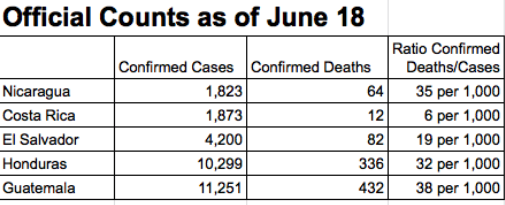

At the moment, there is a debate about numbers. Official statistics concerning COVID-19 in Nicaragua are 1,823 confirmed cases, with 64 deaths. Based on official statistics, this is the lowest number of confirmed cases in Central America, and the second lowest tally of deaths (Costa Rica has only reported 12 deaths).

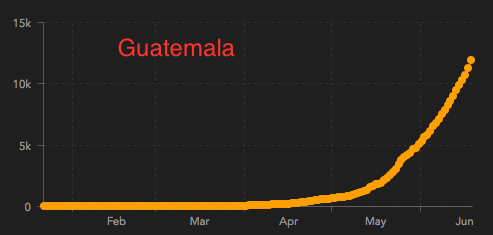

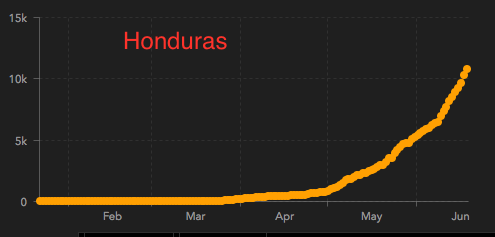

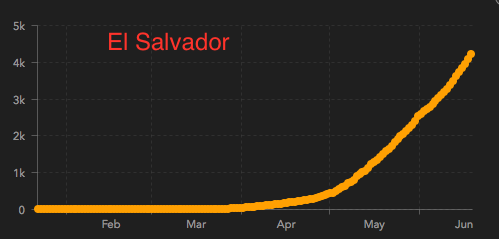

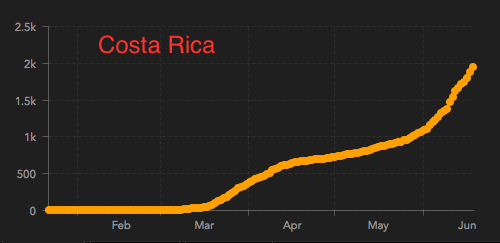

It is not, however, that much of an outlier. El Salvador has 4,200 confirmed cases and 82 deaths with roughly the same number of people, but a population density nearly 6 times that of Nicaragua. As reported in the official data, Nicaragua’s ratio of those dying to confirmed cases is the second highest in the region, after Guatemala. This might simply reflect that people are less likely to get tested and into the health system until they are quite ill. However, the differences between Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala on this count are small. Across the region, access to testing is a huge issue, and in every country across the globe (including the United States), it seems safe to assume that infections are being grossly undercounted. The government’s reporting has been less frequent than that of its neighbors; in comparing the growth curves, for example, one can see that reporting is weekly, not daily. That said, the curve is nearly identical to other countries in the region: relatively flat until May and then taking off. Point is, while the numbers are almost certainly undercounts, as they are everywhere, they hardly stand out as indicators of massive fraud.

That is, until you read the reports of Observatorio Ciudadano COVID-19, an NGO launched in April to offer “independent” estimates of cases, and/or to delegitimize the public health ministry. According to the Observatorio, as of June 10, there are 4,971 suspected cases of COVID-19 and a whopping 1,398 suspected deaths, markedly higher than the official figures. It is, of course, possible, even likely, that the number of cases of people with COVID-19 is that high, or even higher.

Almost every observer of the virus in Latin America would say the undercounts across the region are huge, given the lack of access to testing and the high rate of people who are asymptomatic. For better or worse, we can only compare confirmed cases. If we adopted suspected cases as the framework, the numbers would sky rocket everywhere and would be even more subject to manipulation. The death toll, however, seems way out of proportion, and is put forward with tales of secret burials and massive government cover ups. Even if these breathless tales of conspiracy were true, it seems highly unlikely that Nicaragua has had more than three times the number of COVID deaths as Guatemala, for example, a country with a much larger population living in more crowded quarters.

To be sure, there are several structural features to Nicaragua’s political economy that are in the country’s favor, at least in terms of the initial spread of COVID-19: Lowest population density in Central America, relatively low urbanization rates (over half the population is rural), a history of expansive vaccination campaigns and a parallel infrastructure of community clinics and health care workers, as well as a free healthcare system which has doubled the ratio of doctors to the population over the last 12 years. Alongside that, the country has faced a collapse in tourism and even business travel over the last two years, due to the political crisis, meaning that in the important first weeks of the pandemic, there were fewer international visitors to Nicaragua than elsewhere in the region. These factors, as Magda Lanuza wrote several weeks ago, help to explain the early lower numbers in Nicaragua better than shadowy conspiracies. But while these factors might help explain the slower introduction of COVID-19 to Nicaragua, they do not offer much protection once the virus is introduced and community spread takes root, as is now the case. The healthcare system is impressive, given the constraints the country has faced, but is still under-resourced, and thus ill prepared for a massive number of cases.

So the government should lock everything down, right? Maybe not.

The government’s response is consistent with the fact that, as Quitzé Valenzuela-Stookey writes, Nicaragua is not well equipped for “non-pharmaceutical interventions,” or NPIs. Principally we are talking about social distancing. Nicaragua’s government has received much criticism for not locking-down the economy while keeping schools open. Yet, as Valenzuela-Stookey writes,

The structure of the Nicaraguan economy makes NPIs particularly costly in the short term. Working and learning remotely is impossible for most people in Nicaragua, which has only 2.98 fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 people, compared to 13.44 in Latin America overall. The governmental capacity for fiscal intervention is lower. Its ability to distribute aid directly to businesses and people is limited. This is especially true of workers in the informal sector, which accounts for an estimated 73 percent of non-agricultural employment in Nicaragua. For the 45.5 percent of households classified as food insecure, economic hardship is a critical health issue. The Ortega administration may be justifiably wary of following the example of countries such as Peru, where the growth of infections has been among the highest in the region, despite a strict lockdown implemented early in the early stages of the pandemic.

Ultimately the government in Nicaragua is triangulating several factors - the economic and political costs of locking down the economy, the ability of the country’s health sector to manage cases, and timing. Timing is the critical, ultimately unknowable part. Locking down the economy does not stop the spread of the disease. Social distancing only slows the spread of the disease so that health systems are not overwhelmed. In countries with well-developed health care systems, this might mean that when all is said and done, the death toll will be lower as people buy time for the evolution of new treatments. There is no guarantee that locking down Nicaragua’s economy will have the same effect. Nicaragua’s health care system could be overwhelmed either way, and given the near impossibility of locking down the economy without causing massive unemployment and widespread hunger, this becomes a huge risk.

In that context, the government may well be de-emphasizing the health risks of the novel coronavirus for political reasons. Remember, the country was literally locked down for three months two years ago by opposition forces seeking Ortega’s departure. Those three months broke a record five years of growth and poverty reduction built on governmental policies. Nicaragua has yet to bounce back from that shut down. In light of ongoing U.S. sanctions against Nicaragua, the government would be taking an enormous risk to lock down the country again. This may be a “grim calculus” as Valenzuela-Stookey suggests, but it is also true that the formulation of the problem is taking place within a broader context of crisis brought on by international pressure. Concern for the people of Nicaragua might suggest easing that pressure during this pandemic. But that does not play into the opposition, or U.S. policy goals, very well. Better to discredit.

In Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, where the governments have enforced lock downs and stringent curfews, the list of accompanying human rights abuses is long. Honduras’ government is using mass arrests for curfew violations as cover for rounding up political opponents. El Salvador’s president is using the crisis as a pretext to strengthen his hold on the country’s governing institutions. He has also promoted incarcerating violators of the lock-down in overcrowded detention facilities, where spread of the disease is assured. Nicaragua, on the other hand, released more than 2,800 people from prison as a preventive measure. While it has been reported that some officials and a baseball manager were dismissed from their jobs in reprisal for speaking out about the coronavirus and for demanding personal protective equipment, this sort of response hardly seems comparable to the counterproductive response of incarcerating people in violation of curfew in El Salvador. In any event, Nicaragua remains sanctioned, while the U.S. State Department just certified progress on human rights in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras sufficient to keep funding their militaries and police forces. Seriously.

Maybe one day, U.S. policy makers will end their cynical and often hypocritical practices around human rights and foreign policy. Until then, just remember, that while the government of Nicaragua is probably getting some stuff wrong in the management of this crisis (if you know of a government that got it right, please let me know!), Trump’s State Department is funding most of the “pro-democratic” sources on Nicaragua you read in the Times and the Post, when they bother to write about Nicaragua at all. These are folks whose primary interests lie not in public health, but rather in discrediting the government. Just something to keep in mind.