Read more about InAlienable.Support Quixote Center’s InAlienable program!

InAlienableDaily Dispatch

February 18, 2020

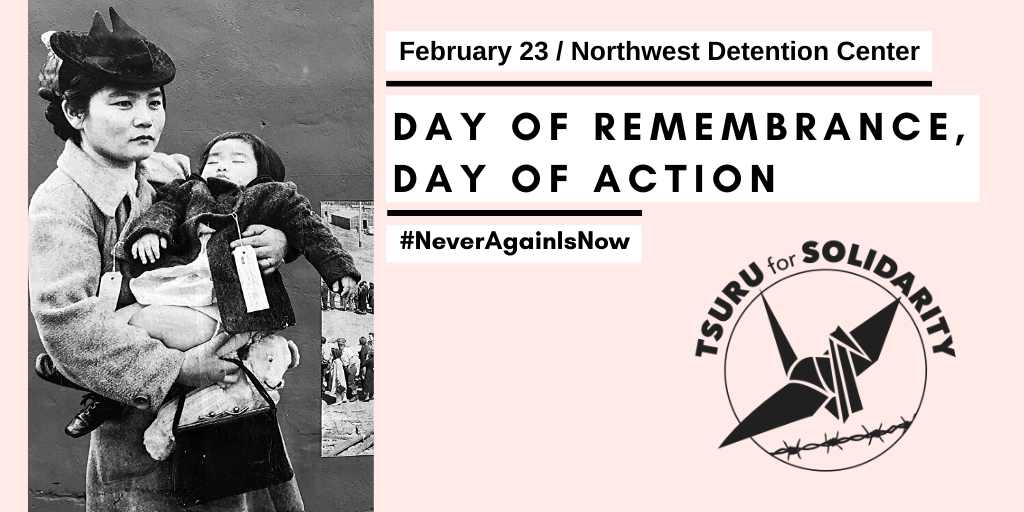

Today is the Day of Remembrance. It was on this day in 1942 that Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066.

The order authorized the secretary of war and any military commander designated by him "to prescribe military areas…from which any or all persons may be excluded." The order does not mention Japanese Americans by name. As a result of this order, some 110,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast were removed from the West Coast, most to inland concentration camps. Public Law 503, enacted a month later, allowed federal courts to enforce the military orders resulting from EO 9066.

Executive Order 9066 was the culmination of decades of abuse targeting Japanese immigrants and their citizen descendants, especially on the West Coast. Immigration from Japan had been suspended, along with other Asian countries, in 1917. Japanese immigrants were not allowed to naturalize and become citizens of the United States until 1952. In California they were even denied the right to purchase land. The detention of Japanese Americans was thus not simply a response to war, but rested upon a long history of exclusionary practices targeting Asian immigrants.

Densho is an organization committed to recording the history of the U.S.detention of Japanese Americans, and keeping that history ever present as a warning about the consequences of racism and nationalism. This week, as part of the commemoration surrounding the Day of Remembrance, Densho is joining immigration activists in demonstrations at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington. From Densho:

The Day of Remembrance, Day of Action at NWDC commemorates the 78th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, and the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans that followed. Today, thousands of immigrants and refugees are confined in similar concentration camps. They are subjected to inhumane conditions, family separations, threats of deportation, and countless indignities.

The Northwest Detention Center (NWDC) in Tacoma, WA is one of the largest immigration prisons in the country, with a capacity to hold up to 1,575 immigrants per day. Up to 200 people, many of whom are seeking asylum, are transferred from the US-Mexico border to the NWDC each month. Other people held at the NWDC have lived in the US for years, in some cases for the majority of their lives. While some are deported after only weeks, some are held for months and even years, awaiting the outcomes of their deportation cases. Few legal protections apply to these civil detainees, and those held are not entitled to an attorney at government expense; approximately 90% of them move forward in their cases unrepresented.

As survivors and descendants of Japanese American WWII incarceration, we stand united with all those who have suffered the atrocities of U.S. concentration camps, past and present, to say, “Stop Repeating History!”

The internment of Japanese Americans in concentration camps during the war is emblematic of the structural contradictions of the modern state system, and the foundational concept of sovereign power expressed within the confines of defined borders. Our tendency is to view the power of sovereignty through parallel concepts of the rule of law and/or constitutional order that strictly define the limits of sovereign authority. However, political theorists (with disparate commitments) like Walter Benjamin, Carl Schmitt and Giorgia Agamben have argued that sovereign power is perhaps better evidenced by the authority to declare “the exception,” or those places where the rule of law is suspended. Agamben argued that this state of exception had become so commonplace as to be the fundamental rule of the modern state. “This is a condition that [Agamben] identifies as one of abandonment, in which the law is in force but has no content or substantive meaning—it is ‘in force without significance.’” We live at the whims of rulers who declare exceptions at will.

Today, on this, the anniversary of the executive order that brought a new generation of concentration camps to the United States, we can see the parallel states of exception being carved out around the world to contain migrants. Millions of people today live in spaces where they have been pushed outside the protections of the rule of law.

Last year Trump declared that people seeking asylum in the U.S. would be forced to “Remain in Mexico” for the duration of their case. What is life like in this state of exception? From the Guardian:

A score or so migrants crouch in the dark corridor of the safe house where they have been waiting for a month. Today, their turn has come to go back on the road again – not across the US border, however, but deeper into Mexico, to save their skins.

Outside, a minivan pulls up, driven by Baptist pastor Lorenzo Ortiz to take the migrants to relative safety, and away from kidnap, extortion and violation.

This is Nuevo Laredo, in the north-west corner of Tamaulipas state, opposite Laredo, Texas, the world’s busiest commercial trans-border hub. The people waiting to board the van have already crossed into the USA, but have been sent back under the Trump administration’s so-called Migrant Protection Protocols - known as “Remain in Mexico” – whereby would be asylum seekers must await their appointed hearing south of the border.

MPP was rolled out in January last year, since when an estimated 57,000 people now wait south of the border for their asylum hearing date. Tens of thousands more are waiting just for the initial application for asylum.

These are the faces behind statistics in a shocking report by Doctors Without Borders (MSF), which found 80% of migrants waiting in Nuevo Laredo under MPP to have been abducted by the mafia, and 45% to have suffered violence or violation.

The door of the safe house opens and blinding sunlight beckons those awaiting, as does Pastor Ortiz, who arrives across the border from Laredo each morning to take a vanload to the larger city of Monterrey, Nuevo León.

There can be no tarrying, explains another local pastor, Diego Robles, from the First Baptist church. “If they walk to the corner of the block,” he says, “they’re likely to be kidnapped.”

Robles knows the risk he runs. Last August, criminals approached Aarón Méndez, a Seventh Day Adventist managing another shelter nearby, demanding he hand over Cubans in his care, whose relatives in the USA might pay high ransoms for their release.

He refused – and has not been seen since, joining the 50,000 disappeared in Mexico’s undeclared war since 2006.

This is the policy of the United States, working with the government of Mexico. Both are constitutional democracies, with clear rules and obligations for the treatment of migrants. Both are signatories to international agreements mandating humane treatment of migrants, including guaranteed access to asylum processes. Both are now placing people in a state of exception to those laws, where they are abused, and many will die.

But the United States is not alone. Across the Atlantic, the European Union has similarly declared a state of exception for migrants - 20,000 of whom live in a refugee camp in Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos:

Before reaching the refugee camp’s main entrance, you turn off the road where the police bus is always parked, then walk up the track that runs beside the perimeter fence. You walk past the military post and the hawkers selling fruit and veg, trainers, cooking utensils, cigarettes, electrical equipment – pretty much everything; past huge stinking mountains of bagged-up rubbish – so much rubbish; and past the worst toilets in the world, overflowing with excrement and plastic.

Then, opposite the hole in the fence where people who don’t want to use the main gate come and go, you turn right, into what they call the Jungle, the olive groves into which the camp has exploded, because it was meant for 3,000 people and now has 20,000. Continue along the winding path, watching out for low-slung washing lines, past the burnt-out olive tree and the tiny tent with the family who always say hello, then turn left up the steep hill that becomes a muddy slide after rain.

Most of the refugees in this camp come from Afghanistan, where the United States has been blowing up houses for 18 years now, though many more are fleeing other conflicts from Syria to Myanmar. Sam Wollastan, writing for the Guardian, visited the camp in order to find some signs of hope - to paint a different picture than the one of constant despair typically projected (a quick review of article titles about the camp at Moria showed most use the adjective “hell” as the main descriptor). He tries - and indeed, there are signs of hope in the very fact that people are trying to build a life in the camp, amidst the violence and utter lack of resources. Within the camp, people organize classes, on everything from the English and German languages to guitar. And yet, outside the camp, Greek nationalists protest their existence and demand the camp's removal — a reminder that Trump is part of a global reactionary force. Other islanders have embraced the refugees, and provide what assistance they can — a reminder that humanity also still has a chance.

Wollastan’s article is framed around his visit to a library launched by one of the camp residents. His name is Zekria. Wollastan reaches out to him to clarify some details on the story to find that Zekria has since fled the camp:

Fearing deportation, he and his family managed to get to mainland Greece, where they are staying in a squat. “It’s cold, there is no electricity, it is the life of refugees,” he says. “I hate the fucking politics of the world.”

He has no money left and will try to find informal work, then perhaps try to cross a land border into Albania or Macedonia. The library and the school in Moria are fine, he says. The team is running them; he is in touch regularly. “I have to go,” he says. “We will speak later, my friend.”

I hate the "fucking politics" of the world too. Moria and Nuevo Laredo stand as indictment to the fictions we continue to weave about the sanctity of the state and the sacrament of nationhood. We’ve been here before.

Never Again Means Now.

If you would like to support the Franciscan Network on Migration, which provides shelter for migrants crossing through Mexico, we are now their fiscal sponsor. You can donate here.

Want to speak out to end the police that is keeping people trapped in Mexico? Veronica Escobar (TX-D) has introduced legislation to defund remain in Mexico and work to extend protections to asylum seekers more generally. The Asylum Seeker Protection Act (H.R. 2662) has 63 co-sponsors. Check to see if your member of Congress is one of them here. If not, call and ask them to co-sponsor the bill!