For this week's Black History Month series at the Quixote Center, we are republishing a post from 2020 on Charlemagne Péralte, who resisted the U.S. occupation of Haiti and remains a legendary symbol of Haitian Liberty today.

The struggle of [hu]man[s] against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting. Milan Kundera, the Book of Laughter and Forgetting

[caption id="attachment_10201" align="alignleft" width="378"] Les Cacos de Leconte, Juillet, 1911 (1954) Obin, Philome, Courtesy of Haitian Art Society[/caption]

Les Cacos de Leconte, Juillet, 1911 (1954) Obin, Philome, Courtesy of Haitian Art Society[/caption]

On June 10, 1920 William Robert Button and Herman Henry Hanneken received the United States Army Medal of Honor. The citations for each reads:

For extraordinary heroism and conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in actual conflict with the enemy near Grande Riviere, Republic of Haiti, on the night of 31 October-l November 1919, resulting in the death of Charlemagne Péralte, the supreme bandit chief in the Republic of Haiti, and the killing, capture and dispersal of about 1,200 of his outlaw followers.

Button and Hanneken’s “conspicuous gallantry” involved entering a rebel camp near Grand Riviere disguised and under cover of night, with 17 members of Haiti’s gendarmerie. They had been tipped to the location, and given guidance, by one of Péralte’s lieutenants, Jean-Baptiste Conzé. There they assassinated Charlemagne Péralte who had been leading the resistance to the U.S. occupation of Haiti since 1917.

[caption id="attachment_8860" align="alignright" width="220"] Photograph courtesy the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale[/caption]

Photograph courtesy the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale[/caption]

The murder of Péralte and defeat of his forces was the cause of celebration in some circles. The next day, R.C. Berkely, reporting from the Marine Headquarters in Cap-Haitien wrote, “It is believed that the death of Charlamagne Péralte will prove a large factor in stopping bandit operations in Haiti.” From Port-au-Prince in December 1919, John H. Russell echoes these congratulations, and notes “the result of this engagement, it is believed, has strengthened the morale and increased the aggressiveness of the Gendarmerie d’Haiti, tending to a higher degree of usefulness in the controlling and keeping the peace in this country, which is so greatly desired.”

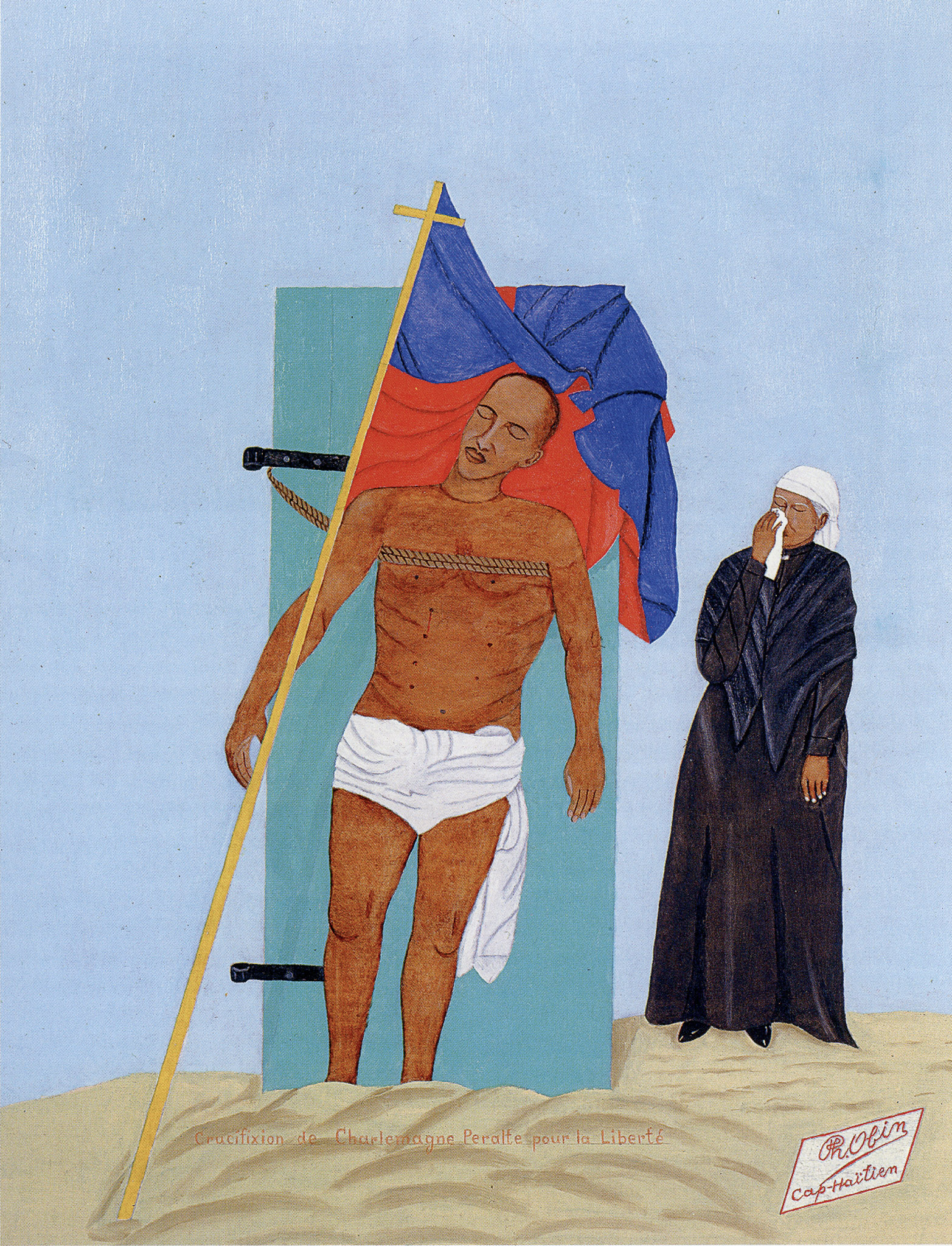

Upon his murder, Péralte’s body was given public viewing in Hinche. He was stripped and tied to a door in a standing position, with a Haitian flag placed such that the pole rested under his arm. His body was photographed, and like the lynching photos circulating in the contemporaneous United States as postcards, the picture was sent throughout Haiti: handed out, dropped from planes, and tacked to boards as a statement of the absolute authority of United States military and allied forces to kill the independent nation of Haiti. This was the “peace….so greatly desired.”.

The ubiquitous presence of the photograph within Haiti guaranteed that Péralte’s sacrifice would be remembered, alongside the brutality of the U.S. occupation. However, back in the U.S., the people were left with only the mere trace of an “imperial encounter” that dissipated into thin air quickly. Button and Hanneken’s Medal of Honor citations conclude: “The successful termination of [their] mission will undoubtedly prove of untold value to the Republic of Haiti,” thus adding another decontextualized set of letters to the ever evolving mythology of the United States as a democratizing “City on the Hill.” In reality, the untold, perhaps unspeakable, value to the Republic of Haiti to evolve from the “termination” of Péralte, was the instantiation of a colonial political economy built on the simple discernment of who lives and who dies; in essence a constitutional determination of who was authorized to kill in defense of the City Bank of New York’s investments in Haiti.

[caption id="attachment_10200" align="alignleft" width="314"] The Crucifixion of Charlemagne Peralte for Freedom, 1970 by Philome Obin, Courtesy of Haitian Art Society[/caption]

The Crucifixion of Charlemagne Peralte for Freedom, 1970 by Philome Obin, Courtesy of Haitian Art Society[/caption]

Of course, the privilege of the colonizer lies in forgetting. Indeed, at home in the metropole, perhaps, the privilege more precisely lies in never having to know the brutality that serves as the foundation for the democratic edifice we pretend to inhabit. As Achille Mbembe writes in Necro Politics, “[d]emocracy, the plantation, and colonial empire are objectively all part of the same historical matrix. The originary and structuring fact lies at the heart of every historical understanding of the violence of the contemporary global order.” [p. 23]. In the United States, like most of Europe, our disassociation from this history serves the power of mythologizing the path to our current moment. We are forever confused about the violence that surrounds us; a violence that is taken as the remnants of unreason standing on the borderlands of a rational, modern democracy, rather than as a constituent element of the really existing (un)democratic order the United States has forged. And so, in the annals of U.S. military history, to the extent Péralte and the rebellion he led is remembered at all, it is only as a footnote to the “heroism, gallantry and intrepidity” of his murderers.

In Haiti people are not allowed to forget. Remembering, to be sure, is not so much an elicitation of dates and names from the past. Remembering is the unavoidable result of remaining inside the institutions of violence begat by the colonial authority’s liaison with a local elite. A syncretic, institutionalized violence that mutates every generation, but never dissipates completely. When colonial authorities blithely note the Gendarmerie d’Haiti’s motivation to higher degrees of “aggressiveness” in keeping the peace in the months after Péralte’s assassination, what they are really celebrating is that Haitian forces, now properly trained, are wiling to murder other Haitians in defense of U.S. capital (and their comprador allies).

When U.S. occupation forces left Haiti in 1934, the Gendarmerie d’Haiti, became the Forces Armées d’Haiti. The army, created by the United States as a counter-insurgency force from the beginning, remained the anvil against which governments backed by the United States smashed any hint of democratic aspiration from Haiti’s popular movements. When the army was not enough, “irregular” forces were called upon to murder and torture and terrorize. Behind it all, U.S. military and intelligence services organized and trained the murderers. For example, Allan Nairn writing for the Nation in 1994, says, “it's universally acknowledged that the FRAPH is an arm of the brutal Haitian security system, which the United States has built and supervised and whose leaders it has trained, and often paid. When I asked Constant, for example, about the anti-Aristide coup, he said that as it was happening Colonel Collins and Donald Terry (the C.I.A. station chief who also ran the SIN) "were inside the [General] Headquarters." But he insisted that this was "normal": The C.I.A. and D.I.A. were always there.'” [emphasis added]

Today the divisions within Haiti remain deep and wide. The governments that have attempted to bridge this divide by inviting Haiti’s impoverished majority to a seat at the table have been either removed or isolated at the hands of armed forces. Standing behind these forces protecting the interests of the wealthy has always been the United States.

So, we can never forget that the people of Haiti’s struggle for democracy, for accountability and for some measure of equity is by necessity also a struggle for independence from the United States.

That struggle is now over a hundred years old.