Two days before the Quixote Center trip to Mexico, a local journalist called me. Louisiana legislators had just drafted a proposal allowing teachers to bring guns to school, and the press wanted a comment from a local teacher. Just ten days after the Uvalde shooting, leaders hastily crafted legislation to demonstrate their resolve in preventing such tragedies in Louisiana.

“As an educator and a parent, Ms. Molina,” said WDSU's anchorman Sherman Desselle. “What's your response to this proposal?”

“Teachers and students have the right to expect that their schools will be safe,” I said. “It is the responsibility of our public officials and security officers to protect us. Shifting that responsibility to teachers is not fair.”

Three days later with the murder of nineteen school children and their two teachers still haunting my country's conscience, I listened as Honduran, Guatemalan, and Ugandan women recounted story after story of their own leaders' abdication of responsibility to protect them and their children in their homelands. Not one of them recited the “looking for a better life” story--the sanitized narrative of seeking economic security in the American Dream. Instead crushing details of sexual violence, extortion, kidnappings and murders of husbands, brothers, sisters, daughters and sons gushed from their mouths in a litany of terror and desperation.

“We would not be here if the police had done their jobs,” said a young Guatemalan mother after escaping the narcotrafficker who kidnapped her and held her hostage for three months of rapes and beatings.

Even as these women flee an astounding level of physical and sexual violence at home, the risk of such violence is extremely high on the road north. Not naïve, migrant women prepare as best as they can. They told us of being “vaccinated” for the journey—taking oral contraceptives to prevent pregnancy if they are raped along the way.

Each woman sighed as she recounted countless and futile attempts to seek protection and justice from law enforcement and human rights organizations. Each voiced the devastating lack of results, the dismissiveness of officials or even worse…the divulgence of their reports to gangs who retaliated with more intimidation, threats and violence.Every migrant woman's story illustrated the scars of an institutional failure to protect them and their children, and the very name and walls of their temporary refuge, the Franciscan migrant shelter La 72, serve as poignant reminders that this failure is not merely anecdotal but historic and well-documented.

La 72 is named in memory of 72 migrants who were massacred in Tamaulipas, Mexico in 2010. Today women and children fill the chapel of La 72, a memorial to the murdered migrants. Resting on floor mats with their backpacks and water bottles at their sides, they face the chapel's altar wall where seventy-two crosses remind them of the tragic fate of their predecessors. Each cross bears the name of a murdered migrant and the flag of his/her country. Some have only the flag… “because we still don't know the names of all the victims,” explained Alejandra Conde, La 72's Coordinator of Structural Change.

La 72 is named in memory of 72 migrants who were massacred in Tamaulipas, Mexico in 2010. Today women and children fill the chapel of La 72, a memorial to the murdered migrants. Resting on floor mats with their backpacks and water bottles at their sides, they face the chapel's altar wall where seventy-two crosses remind them of the tragic fate of their predecessors. Each cross bears the name of a murdered migrant and the flag of his/her country. Some have only the flag… “because we still don't know the names of all the victims,” explained Alejandra Conde, La 72's Coordinator of Structural Change.

The killings are suspected to be the result of collusion between Mexican police officers and drug cartel leaders. In 2011, twelve Mexican police officers were detained on homicide charges in the case. But not until May of this year was anyone convicted and sentenced for crimes against the migrants. Even then, when a Mexican judge finally convicted eighteen drug cartel leaders, it was for the abduction, not of the murders, of the 72 migrants.

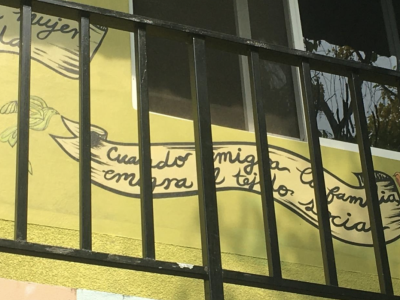

The walls of La 72 do not let migrants or visitors forget the complicity of our nation's leaders in the heartbreaking tragedy of forced migrations.

Another wall at La 72 features a map of the Americas. Former US President Donald Trump's orange hair erupts into flames from which Latin American migrants appear. “Trump,” the mural admonishes in Spanish, “You will be the one who lights the fire of resistance of the peoples.” In the bottom right corner, the declaration is in Spanglish, “20 enero 2021 got out!!! Mr. Trump Fuera JOH.” The first is a reference to the last day of Trump's term in office. The second is a popular Honduran political chant meaning “Out with JOH," initials of former (2014-2022) Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez.

Another wall at La 72 features a map of the Americas. Former US President Donald Trump's orange hair erupts into flames from which Latin American migrants appear. “Trump,” the mural admonishes in Spanish, “You will be the one who lights the fire of resistance of the peoples.” In the bottom right corner, the declaration is in Spanglish, “20 enero 2021 got out!!! Mr. Trump Fuera JOH.” The first is a reference to the last day of Trump's term in office. The second is a popular Honduran political chant meaning “Out with JOH," initials of former (2014-2022) Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez.

Trump's pressure on Mexico to militarize the border created even more dangerous conditions for migrants especially in light of historic corruption among Mexican police—as in the case of the Tamaulipas massacre.

As for Hernandez, in April, the US government ordered his arrest and extradition on charges of alleged drug-trafficking conspiracy. Last year Hernandez's brother, “Tony,” a former Honduran congressman, was sentenced in US court to life in prison for drug trafficking and bribery. The US Department of Justice contends that the former president and US ally allegedly received millions of dollars from cartel leaders in exchange for protection from arrest. Juan Orlando Hernandez, they say, allegedly:

leveraged the Government of Honduras' law enforcement, military, and financial resources…to protect drug traffickers…including his brother…from investigation, arrest, and extradition; caused sensitive law enforcement and military information to be provided to drug traffickers to aid them in transporting tons of cocaine through Honduras, bound for the United States; directed heavily-armed members of the Honduran National Police and Honduran military to protect drug shipments as they transited Honduras; and sanctioned brutal violence.

- 1995: The Franciscan Province initiates attention to migrants.

- 8/23/2010: Massacre, San Fernando, Tam [Tamaulipas where 72 migrants were killed].

- 4/2011: Mass graves in Northern Mexico 400 tortured bodies

- 4/23/2011: La 72 shelter for migrants [opens]

- 2011: CNDH [Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos—the National Commission for Human Rights in Mexico] reports that more than 20,000 migrants were kidnapped in Mexico

- 5/2012: Mutilated bodies in Cadereyta, NL [Nuevo León]

- 1/5/2013: Attack at the train in Barrancas, Ver. [Vera Cruz]

- 8/25/2013: Deaths of 12 people from a train derailment in Tembladera

The exterior wall of the migrant men's barracks bears the image of a young migrant who once stayed at La 72 and was killed after leaving the shelter to head north. “Our demand is minimal: JUSTICE,” reads the inscription across his chest.

The exterior wall of the migrant men's barracks bears the image of a young migrant who once stayed at La 72 and was killed after leaving the shelter to head north. “Our demand is minimal: JUSTICE,” reads the inscription across his chest.

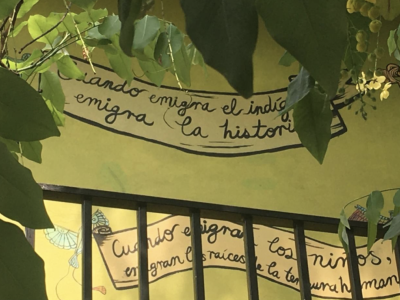

The walls of La 72 tell the stories of tragedy and exploitation, but they also tell tales of hope, strength, resourcefulness and solidarity.

The walls of La 72 tell the stories of tragedy and exploitation, but they also tell tales of hope, strength, resourcefulness and solidarity.

Most of the shelters we visited display such road maps offering valuable information for migrants trying to navigate the ecosystem of exploitation and aid that lies ahead. Map key symbols include: roads, fees (approx.. $100), danger zones, assaults & kidnappings, migrant houses, soup kitchens, rivers, border walls.

Tomorrow I return to school where teachers will be preparing for students. We will plaster our classroom walls with historic figures, helpful information and inspirational quotes. Much like the volunteer artists at La 72, we hope our efforts can inform, guide, and encourage those who walk the hallways to navigate their paths carefully and pursue their dreams. We will remember our colleagues in Uvalde who will be doing the same. ![]()

Hispanics make up over 80% of the population in Uvalde, where a large immigrant community resides. It is painfully ironic that many of those families, like the ones at La 72, may have migrated to escape violence.

So many migrants at La 72 and the other shelters that we visited voiced their deepest hopes to make it to the US…not because of its wealth but because of their perception of the US as “a country where the law is enforced,” a country where they and their children might be safe from the violence in their own countries and the violence they face on their journey.

I pray that they will one day be able to breathe the sweet relief of being safe. That they will one day be able to stop running and hiding in fear. I, like those at La 72, will continue to hope and to believe in the strength of community and solidarity. But like those at La 72, I will also continue to hold our leaders accountable for the systemic failure that strips our families of dignity and peace.

Migrant families, like US school children and teachers, have the right to expect that their communities will be safe—whether in their native lands or in the US. Political leaders and law enforcement officers are paid to protect our communities. When they fail us through corruption, apathy, racism, or incompetence, we will not perpetuate a narrative that shifts blame and responsibility to us. We will continue to hold them accountable, and I will not be packing a gun to school.

![“When [a] youth migrates, hope migrates.”](https://quixote.org/files/styles/pfp_gallery_thumb/public/pfp_gallery/la-72-mural-gallery-2.png)